Chapter 13 Ensemble learning

Bagging, random forests and, boosting methods are the main methods of ensemble learning - a machine learning method where multiple models are trained to solve the same problem. The main idea is that, instead of using all features (predictors) in one complex base model running on the whole data, we combine multiple models each using selected number of features and subsections of the data. With this, we can have a more robust learning system.

Often, these single models are called a “weak” models. This is because, individually, they are imperfect due to their lack of complexity and/or their use of only a subsection of the data. The “weakness” can be thought of their insignificant contribution to the prediction problem. A weak classifier, for example, is that its error rate is only slightly better than a random guessing. When we use a single robust model, poor predictors would be eliminated in the training procedure. However, although each poor predictor has a very small contribution in training, their combination represented in weak models would be huge.

Ensemble learning systems help these poor predictors have their “voice” in the training process by keeping them in the system rather than eliminating them. That’s the main reason why ensemble methods are robust and the main tools of machine learning.

13.1 Bagging

Bagging gets its name from Bootstrap aggregating of trees. It works with a few simple arguments:

- Select number of trees

B, and the tree depthD, - Create a loop

Btimes, - In each loop, (a) generate a bootstrap sample from the original data; (b) estimate a tree of depth

Don that sample.

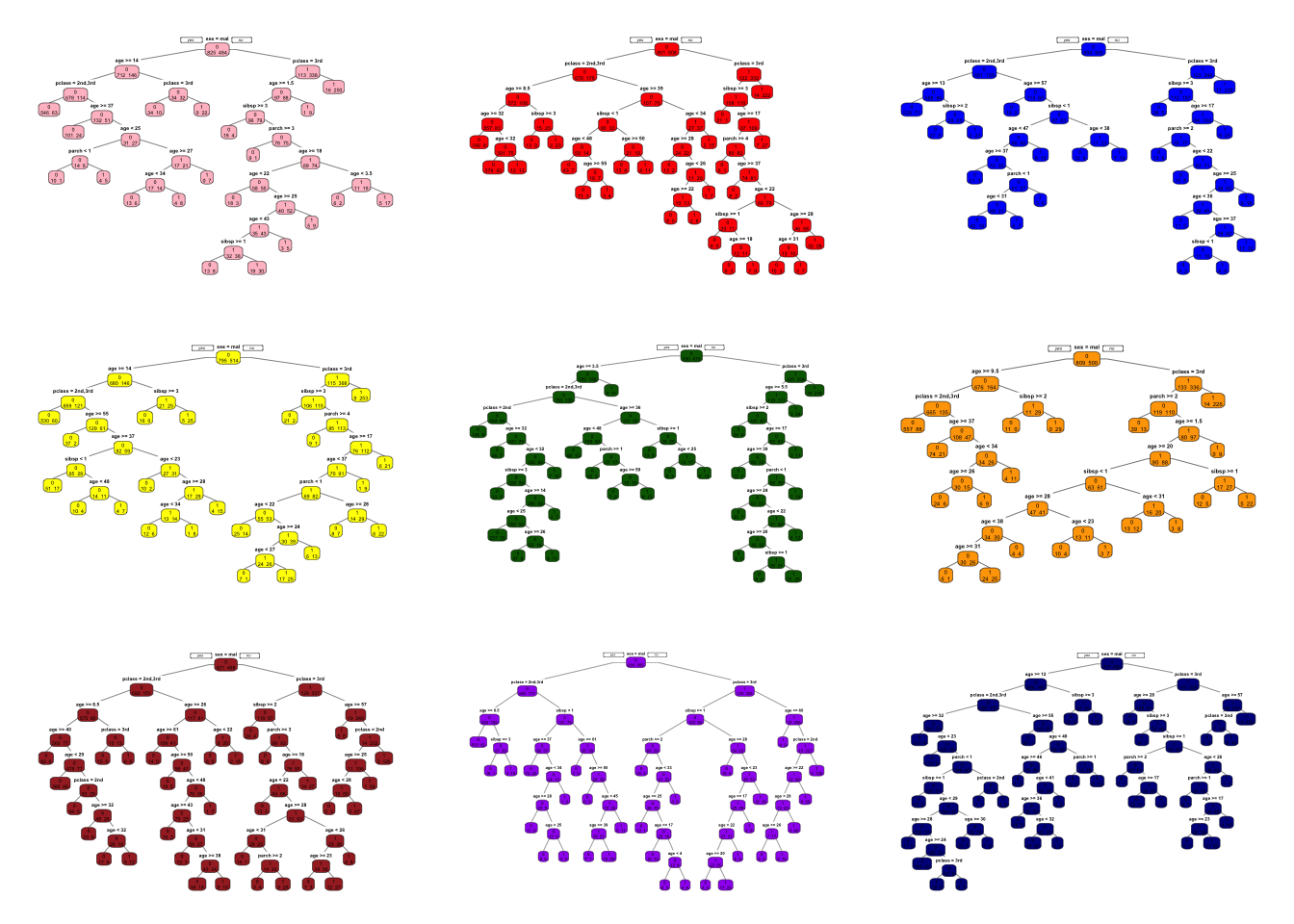

Let’s see an example with the titanic dataset:

library(PASWR)

library(rpart)

library(rpart.plot)

data(titanic3)

# This is for a set of colors in each tree

clr = c("pink","red","blue","yellow","darkgreen",

"orange","brown","purple","darkblue")

n = nrow(titanic3)

par(mfrow=c(3,3)) # this is for putting all plots together

for(i in 1:9){ # Here B = 9

set.seed(i)

idx = sample(n, n, replace = TRUE) #Bootstrap sampling with replacement TRUE

tr <- titanic3[idx,]

cart = rpart(survived~sex+age+pclass+sibsp+parch, data = tr,

cp=0, method="class") # Unpruned

prp(cart, type=1, extra=1, box.col=clr[i])

}

What are we going to do with these 9 trees?

In regression trees, the prediction will be the average of the resulting predictions. In classification trees, we take a majority vote.

Since averaging a set of observations by bootstrapping reduces the variance, the prediction accuracy increases. More importantly, compared to CART, the results would be much less sensitive to the original sample. As a result, they show impressive improvement in accuracy.

Below, we have an algorithm that follows the steps for bagging in classification. Let’s start with a single tree and see how we can improve it with bagging:

#test/train split

set.seed(1)

ind <- sample(nrow(titanic3), nrow(titanic3)*0.8)

train <- titanic3[ind, ]

test <- titanic3[-ind, ]

#Single tree

cart <- rpart(survived ~ sex + age + pclass + sibsp + parch,

data = train, method="class") #Pruned

phat1 <- predict(cart, test, type = "prob")

#AUC

pred_rocr <- prediction(phat1[,2], test$survived)

auc_ROCR <- performance(pred_rocr, measure = "auc")

auc_ROCR@y.values[[1]]## [1] 0.8352739Let’s do the bagging:

B = 100 # number of trees

phat2 <- matrix(0, B, nrow(test)) #Container

# Loop

for(i in 1:B){

set.seed(i) # to make it reproducible

idx <- sample(nrow(train), nrow(train), replace=TRUE)

dt <- train[idx,]

cart_B <- rpart(survived ~ sex + age + pclass + sibsp + parch,

data = dt, method="class") #Pruned

phat2[i,] <- predict(cart_B, test, type = "prob")[, 2]

}

dim(phat2)## [1] 100 262You can see in that phat2 matrix is \(100 \times 262\). Each column is representing the predicted probability that survived = 1. We have 100 trees (rows in phat2) and 100 predicted probabilities for each the observation in the test data. The only job we will have now to take the average of 100 predicted probabilities for each column.

# Take the average

phat_f <- colMeans(phat2)

#AUC

pred_rocr <- prediction(phat_f, test$survived)

auc_ROCR <- performance(pred_rocr, measure = "auc")

auc_ROCR@y.values[[1]]## [1] 0.8577337Hence, we have a slight improvement over a single tree. But the main idea behind bagging is to reduce the variance in prediction. The reason for this reduction is simple: we take the mean prediction of all bootstrapped samples. Remember, when we use a simple tree and make 500 bootstrapping validations, each one of them gives a different MSPE (in regressions) or AUC (in classification). We did that many times before. The difference now is that we average yhat in regressions or phat in classifications (or yhat with majority voting). This reduces the prediction uncertainty drastically. To test this, we have to run the same script multiple times and see how AUC with bagging would vary in each run relative to a single tree. Final point is that, B the number of trees could be a hyperparameter. That is, if we set less or more trees, what would happen to AUC?

All these issues bring us to another model, random forest:

13.2 Random Forest

Random Forest = Bagging + subsample of covariates at each node. We have done the first part above, and to some degree, it’s understandable. But, “subsampling covariates at each node” is new.

We will use the Breiman and Cutler’s Random Forests for Classification and Regression: randomForest()(Breiman and Cutler 2004).

Here are the steps and the loop structure:

- Select number of trees

ntree, subsampling parametermtry, and the tree depthmaxnodes, - Create a loop

ntreetimes, - In each loop, (a) generate a bootstrap sample from the original data; (b) estimate a tree of depth

maxnodeson that sample, - But, for split in the tree (this is our second loop), randomly select

mtryoriginal covariates and do the split among those.

Hence, bagging is a special case of random forest, with mtry = number of features (\(P\)).

Let’s talk about this “subsampling covariates at each node”. When we think on this idea little bit more, we can see the rationale: suppose there is one very strong covariate in the sample. Almost all trees will use this covariate in the top split. All of the trees will look quite similar to each other. Hence the predictions will be highly correlated. Averaging many highly correlated quantities does not lead to a large reduction in variance. Random forests decorrelate the trees. Hence Random Forest further reduces the sensitivity of trees to the data points that are not in the original dataset.

How are we going to pick mtry? In practice, default values are mtry = \(P/3\) in regression and mtry = \(\sqrt{P}\) classification. (See mtry in ?randomForest). Note that, with this parameter (mtry), we can run a pure bagging model with randomForest(), instead of rpart(), if we set mtry = \(P\).

You can think of a random forest model as a robust version of CART models. There are some default parameters that can be tuned in randomForest(), which lead to the same (two ways) way to grow a tree as in CART. Hastie et al. argues that (Elements of Statistical Learning, 2009, p.596) the problem of overfitting is not that large in random forests. As the depth of a tree increases (maxnodes, see below), overfitting is argued to be minor.

Segal (2004) demonstrates small gains in performance by controlling the depths of the individual trees grown in random forests. Our experience is that using full-grown trees seldom costs much, and results in one less tuning parameter. Figure 15.8 shows the modest effect of depth control in a simple regression example. (Hastie et al., 2009, p.596)

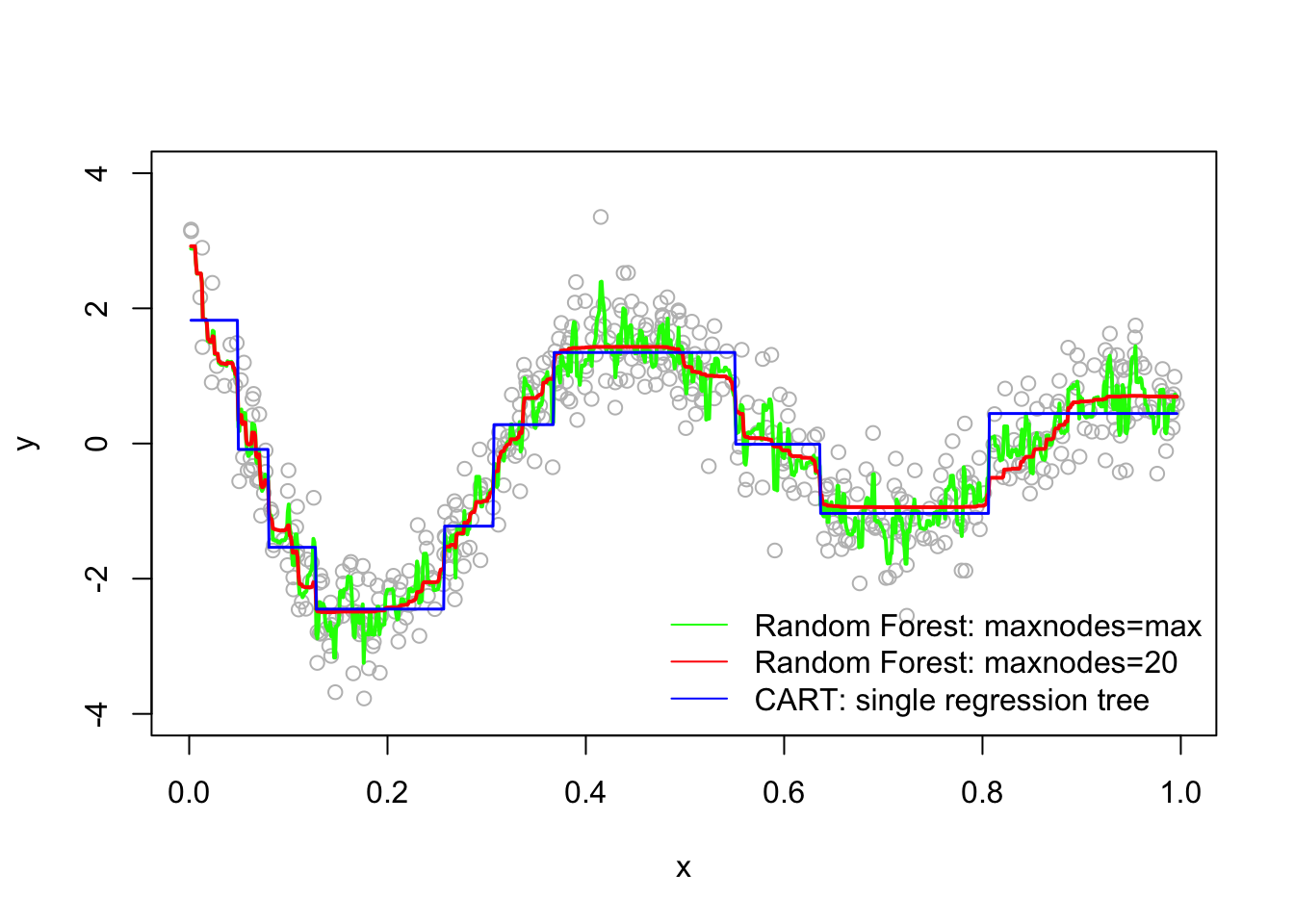

Let’s start with a simulation to show random forest and CART models:

library(randomForest)

# Note that this is actually Bagging since we have only 1 variable

# Our simulated data

set.seed(1)

n = 500

x <- runif(n)

y <- sin(12*(x+.2))/(x+.2) + rnorm(n)/2

# Fitting the models

fit.tree <- rpart(y~x) #CART

fit.rf1 <- randomForest(y~x) #No depth control

fit.rf2 <- randomForest(y~x, maxnodes=20) # Control it

# Plot observations and predicted values

z <- seq(min(x), max(x), length.out=1000)

par(mfrow=c(1,1))

plot(x, y, col="gray", ylim=c(-4,4))

lines(z, predict(fit.rf1, data.frame(x=z)), col="green", lwd=2)

lines(z, predict(fit.rf2, data.frame(x=z)), col="red", lwd=2)

lines(z, predict(fit.tree, data.frame(x=z)), col="blue", lwd=1.5)

legend("bottomright", c("Random Forest: maxnodes=max","Random Forest: maxnodes=20",

"CART: single regression tree"),

col=c("green","red", "blue"),

lty=c(1,1,1), bty = "n" )

The random forest models are definitely improvements over CART, but which one is better? Although random forest models should not overfit when increasing the number of trees (ntree) in the forest, it seems that there is no consensus on the depth of tree, maxnodes in the field. Hence, the question for practitioners becomes whether it would be possible to improve the model’s performance if we tune Random Forest parameters?

Let’s use out-of-bag (OOB) MSE to tune Random Forest parameters in our case to see if there is any improvement.

# OOB-MSE

a <- randomForest(y~x)

a##

## Call:

## randomForest(formula = y ~ x)

## Type of random forest: regression

## Number of trees: 500

## No. of variables tried at each split: 1

##

## Mean of squared residuals: 0.3891797

## % Var explained: 80.43a$mse[500]## [1] 0.3891797Let’s control our tree depth:

maxnode <- c(10,50,100,500)

for (i in 1:length(maxnode)) {

a <- randomForest(y~x, maxnodes = maxnode[i])

print(c(maxnode[i], a$mse[500]))

}## [1] 10.0000000 0.3894515

## [1] 50.0000000 0.3353509

## [1] 100.0000000 0.3592304

## [1] 500.000000 0.392889We can see that OOB-MSE is smaller with maxnodes = 50. Of course we can have a more refined sequence of maxnodes series to test. Similarly, we can select parameter mtry with a grid search.

We need to understand that there is no need to perform cross-validation in Random Forest. By bootstrapping, each tree uses around 2/3 of the observations. The remaining 1/3 of observations are referred to as the out-of-bag (OOB) observations, which are used for out-sample predictions. All performance measures for the model are based on these OOB predictions including MSE in case of regressions.

We can manually calculate mse_oob[500]

# OOB-MSE

a <- randomForest(y~x)

a##

## Call:

## randomForest(formula = y ~ x)

## Type of random forest: regression

## Number of trees: 500

## No. of variables tried at each split: 1

##

## Mean of squared residuals: 0.3945894

## % Var explained: 80.16a$mse[500]## [1] 0.3945894# Manually

mean((a$predicted - y)^2)## [1] 0.3945894In a bagged model we set mtry = \(P\). If we want, we can tune the maximum number of terminal nodes that trees in the forest can have, maxnodes. If it is not specified, trees are grown to the maximum possible value, which is the number of observations. In practice, although there is no 100% consensus, the general approach is to grow the trees with the maximum number of terminal nodes. We have shown that, however, with a cross-validation, this parameter can be set so that OOB-MSE would be smaller than the one with the maximum maxnodes.

In a random forest model, in addition to maxnodes (which is again set to \(n\)), we can tune the number of variables randomly sampled as candidates at each split, mtry. If we don’t set it, the default values for mtry are square-root of \(p\) for classification and \(p/3\) in regression, where \(p\) is number of variables/features. If we want, we can tune both parameters with cross-validation. The effectiveness of tuning random forest models in improving their prediction accuracy is an open question in practice.

Bagging and random forest models tend to work well for problems where there are important nonlinearities and interactions. More importantly, they are robust to the original sample and more efficient than single trees. There are several tables in the Breiman’s original paper (Breiman 2001a) comparing the performance of random forest and single tree (CART) models.

However, the results would be less intuitive and difficult to interpret. Nevertheless, we can obtain an overall summary of the importance of each covariates using SSR (for regression) or Gini index (for classification). The index records the total amount that the SSR or Gini is decreased due to splits over a given covariate, averaged over all ntree trees.

rf <- randomForest(as.factor(survived) ~ sex + age + pclass + sibsp + parch,

data=titanic3, na.action = na.omit)

importance(rf)## MeanDecreaseGini

## sex 129.76641

## age 63.36484

## pclass 53.64906

## sibsp 19.17399

## parch 17.53605We will see a several applications on CART, bagging and Random Forest in the lab section covering this chapter.

13.3 Boosting

Boosting is an ensemble method that combines a set of “weak learners” into a strong learner to improve the prediction accuracy in self-learning algorithms. In boosting, the constructed iteration selects a random sample of data, fits a model, and then train sequentially. In each sequential model, the algorithm learns from the weaknesses of its predecessor (predictions errors) and tries to compensate for the weaknesses by “boosting” the weak rules from each individual classifier. The first original boosted application was offered in 1990 by Robert Schapire (1990) (Schapire 1990).12

Today, there are many boosting algorithms that are mainly grouped in the following three types:

- Gradient descent algorithm,

- AdaBoost algorithm,

- Xtreme gradient descent algorithm,

We will start with a general application to show the idea behind the algorithm using the package gbm, Generalized Boosted Regression Models

13.3.1 Sequential ensemble with gbm

Similar to bagging, boosting also combines a large number of decision trees. However, the trees are grown sequentially without bootstrap sampling. Instead each tree is fit on a modified version of the original dataset, the error.

In regression trees, for example, each tree is fit to the residuals from the previous tree model so that each iteration is focused on improving previous errors. This process would be very weird for an econometrician. The accepted model building practice in econometrics is that you should have a model that the errors (residuals) should be orthogonal (independent from) to covariates. Here, what we suggest is the opposite of this practice: start with a very low-depth (shallow) model that omits many relevant variables, run a linear regression, get the residuals (prediction errors), and run another regression that explains the residuals with covariates. This is called learning from mistakes.

Since there is no bootstrapping, this process is open to overfitting problem as it aims to minimize the in-sample prediction error. Hence, we introduce a hyperparameter that we can tune the learning process with cross-validation to stop the overfitting and get the best predictive model.

This hyperparameter (shrinkage parameter, also known as the learning rate or step-size reduction) limits the size of the errors.

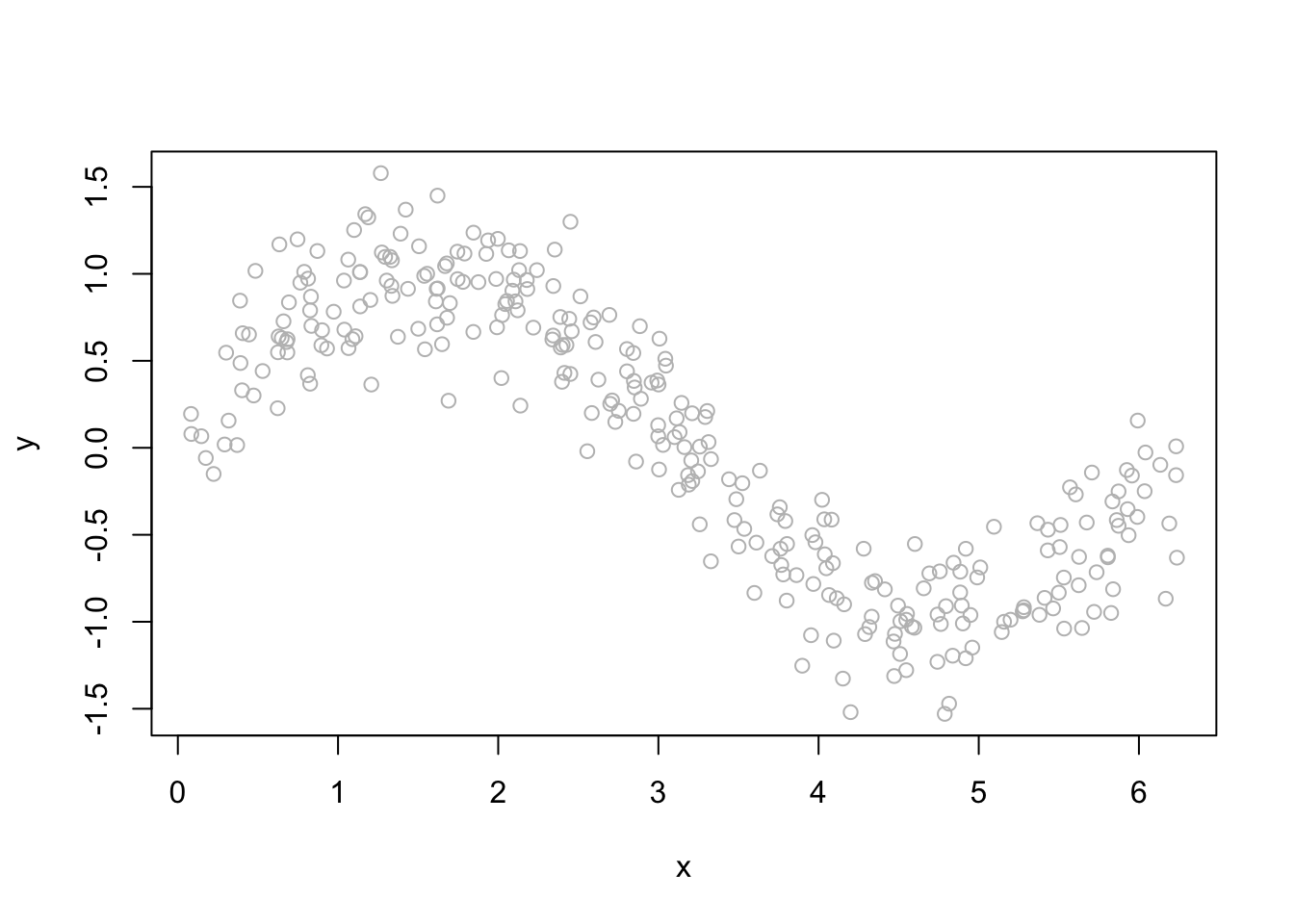

Let’s see the whole process in a simple example inspired by Freakonometrics (Charpentier 2018a):

# First we will simulate our data

n <- 300

set.seed(1)

x <- sort(runif(n) * 2 * pi)

y <- sin(x) + rnorm(n) / 4

df <- data.frame("x" = x, "y" = y)

plot(df$x, df$y, ylab = "y", xlab = "x", col = "grey")

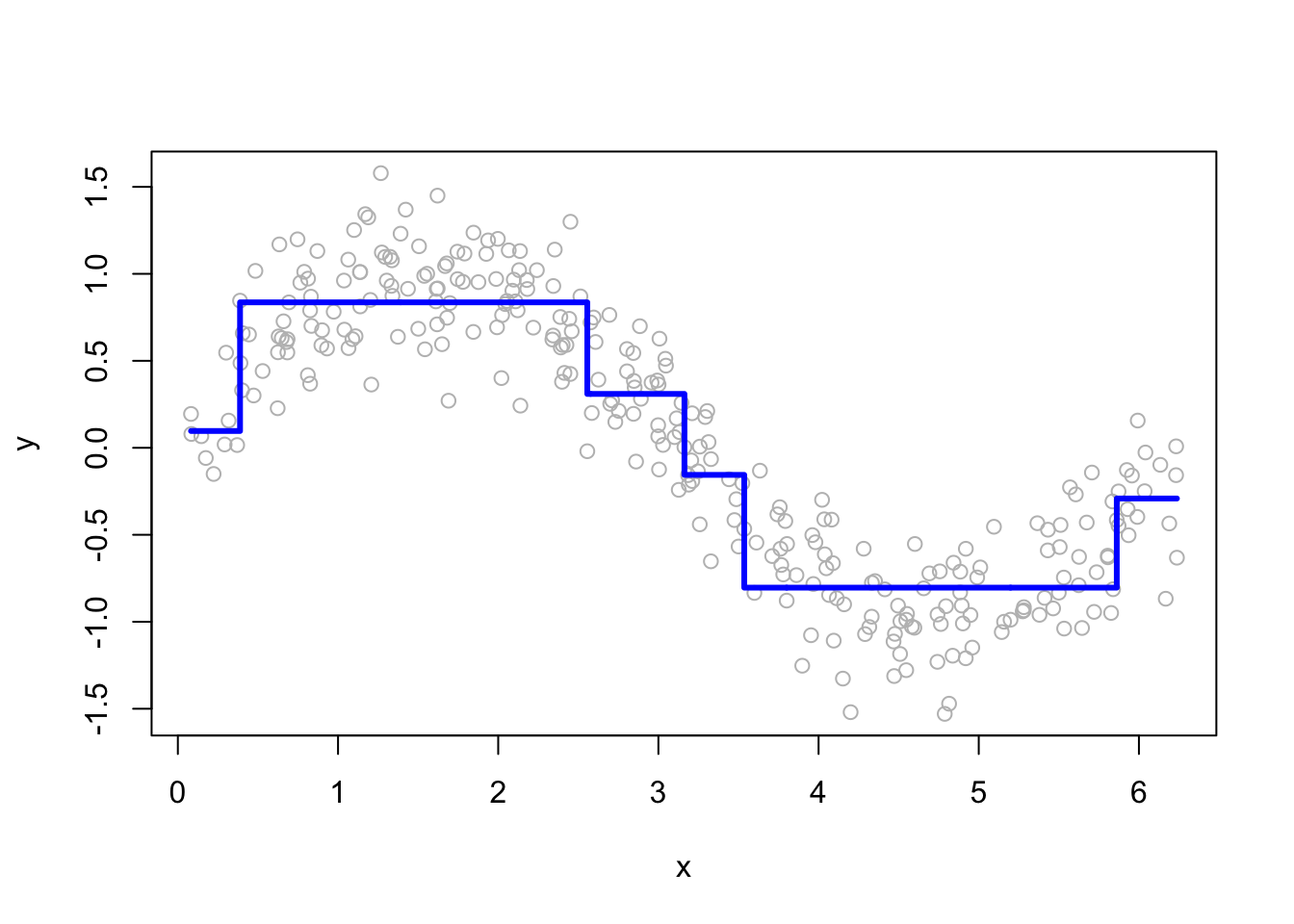

We will “boost” a single regression tree:

Step 1: Fit the model by using in-sample data

# Regression tree with rpart()

fit <- rpart(y ~ x, data = df) # First fit: y~x

yp <- predict(fit) # using in-sample data

# Plot for single regression tree

plot(df$x, df$y, ylab = "y", xlab = "x", col = "grey")

lines(df$x, yp, type = "s", col = "blue", lwd = 3)

Now, we will have a loop that will “boost” the model. What we mean by boosting is that we seek to improve yhat, i.e. \(\hat{f}(x_i)\), in areas where it does not perform well by fitting trees to the residuals.

Step 2: Find the “error” and introduce a hyperparameter h.

h <- 0.1 # shrinkage parameter

# Add this adjusted prediction error, `yr` to our main data frame

# which will be our target variable to predict later

df$yr <- df$y - h * yp

# Store the "first" predictions in YP

YP <- h * yp Note that if h=1, it would give us usual “residuals”. Hence, h controls for “how much error” we would like to reduce.

Step 3: Now, predict the “error” in a loop that repeats itself many times.

# Boosting loop for t times (trees)

for (t in 1:100) {

fit <- rpart(yr ~ x, data = df) # here it's yr~x.

# We try to understand the prediction error by x's

yp <- predict(fit, newdata = df)

# This is your main prediction added to YP

YP <- cbind(YP, h * yp)

df$yr <- df$yr - h * yp # errors for the next iteration

# i.e. the next target to predict!

}

str(YP)## num [1:300, 1:101] 0.00966 0.00966 0.00966 0.00966 0.00966 ...

## - attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2

## ..$ : chr [1:300] "1" "2" "3" "4" ...

## ..$ : chr [1:101] "YP" "" "" "" ...Look at YP now. We have a matrix 300 by 101. This is a matrix of predicted errors, except for the first column. So what?

# Function to plot a single tree and boosted trees for different t

viz <- function(M) {

# Boosting

yhat <- apply(YP[, 1:M], 1, sum) # This is predicted y for depth M

plot(df$x, df$y, ylab = "", xlab = "") # Data points

lines(df$x, yhat, type = "s", col = "red", lwd = 3) # line for boosting

# Single Tree

fit <- rpart(y ~ x, data = df) # Single regression tree

yp <- predict(fit, newdata = df) # prediction for the single tree

lines(df$x, yp, type = "s", col = "blue", lwd = 3) # line for single tree

lines(df$x, sin(df$x), lty = 1, col = "black") # Line for DGM

}

# Run each

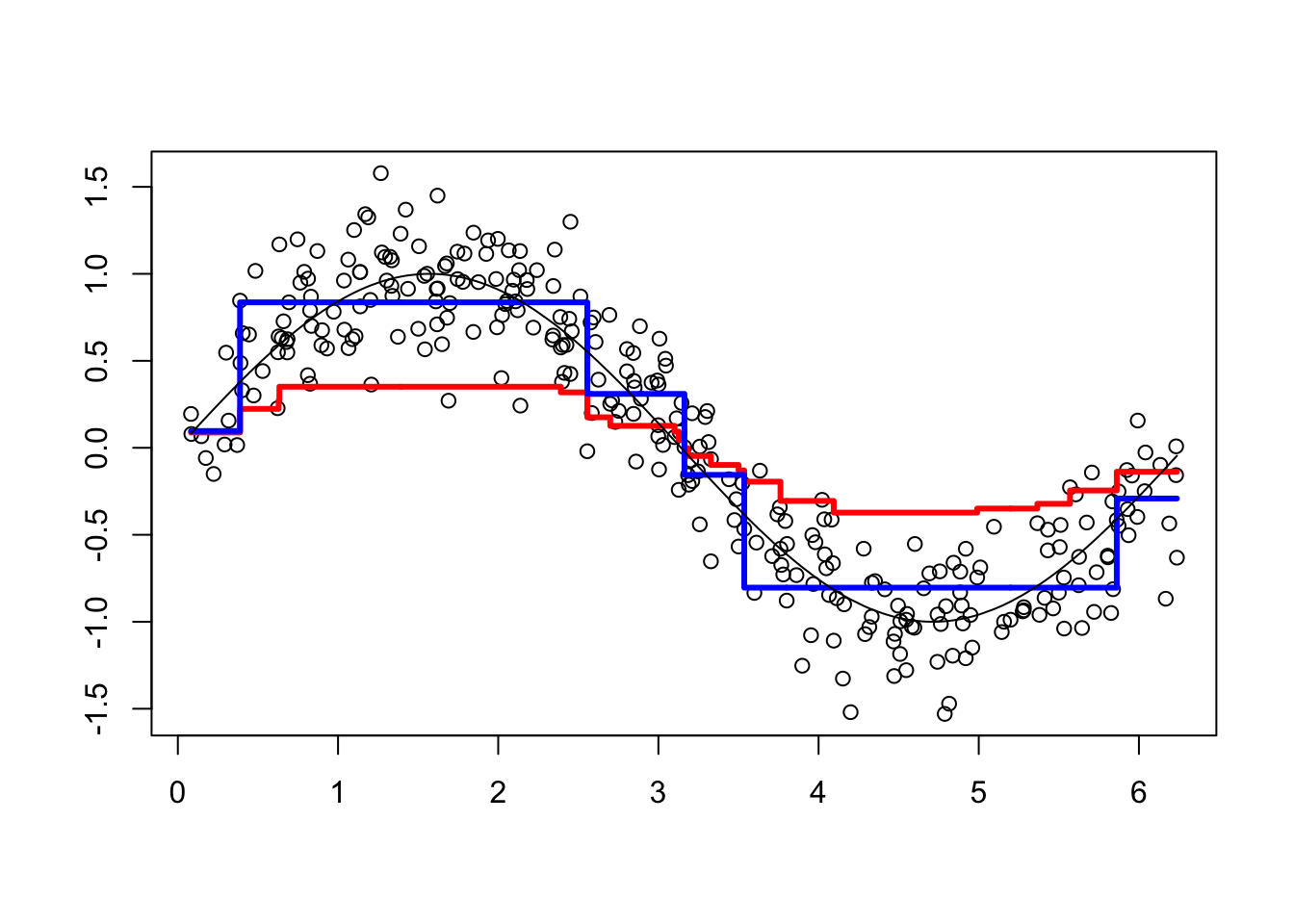

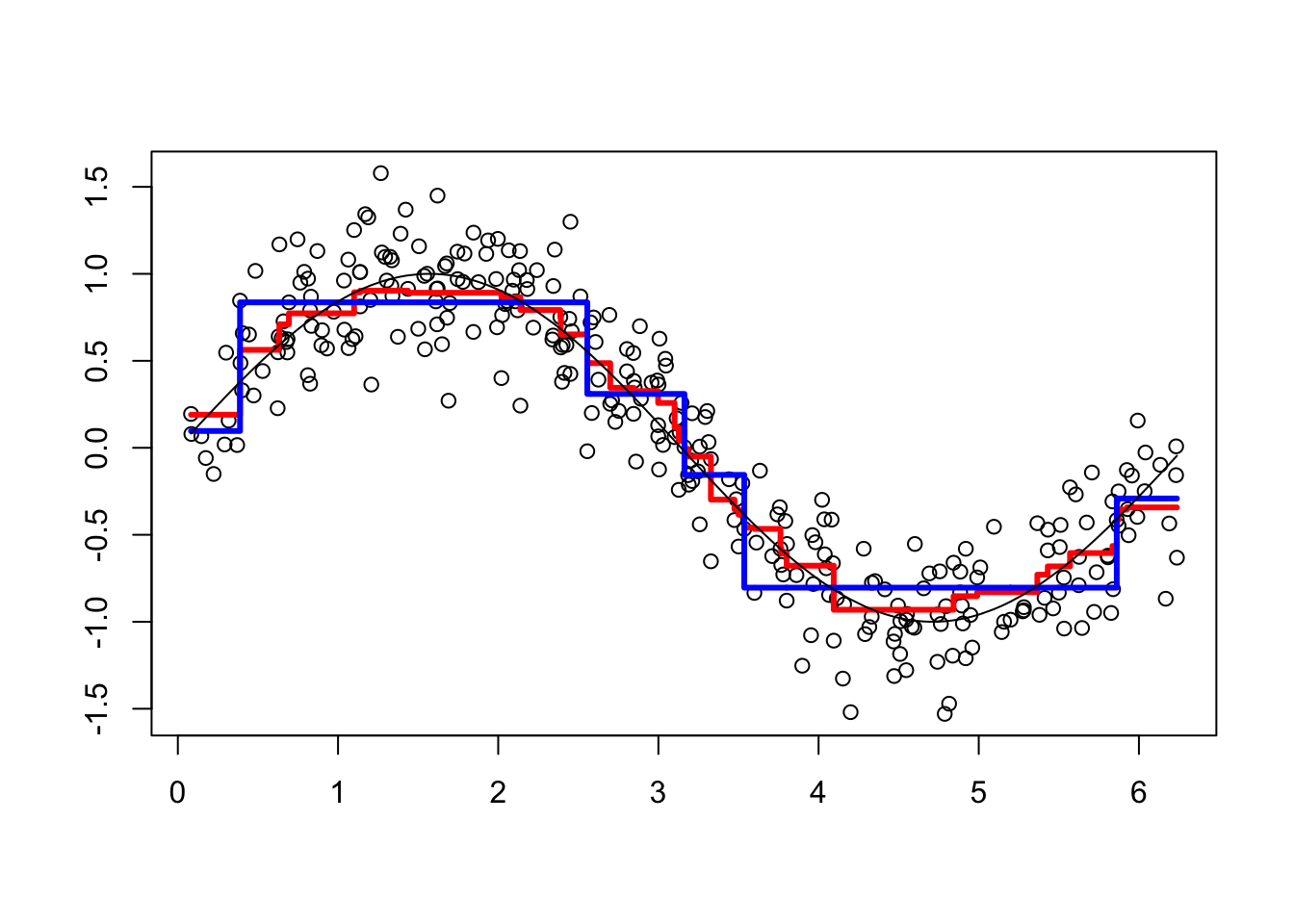

viz(5)

viz(101)

Each of 100 trees is given in the YP matrix. Boosting combines the outputs of many “weak” learners (each tree) to produce a powerful “committee”. What if we change the shrinkage parameter? Let’s increase it to 1.8.

h <- 1.8 # shrinkage parameter

df$yr <- df$y - h*yp # Prediction errors with "h" after rpart

YP <- h*yp #Store the "first" prediction errors in YP

# Boosting Loop for t (number of trees) times

for(t in 1:100){

fit <- rpart(yr~x, data=df) # here it's yr~x.

yhat <- predict(fit, newdata=df)

df$yr <- df$yr - h*yhat # errors for the next iteration

YP <- cbind(YP, h*yhat) # This is your main prediction added to YP

}

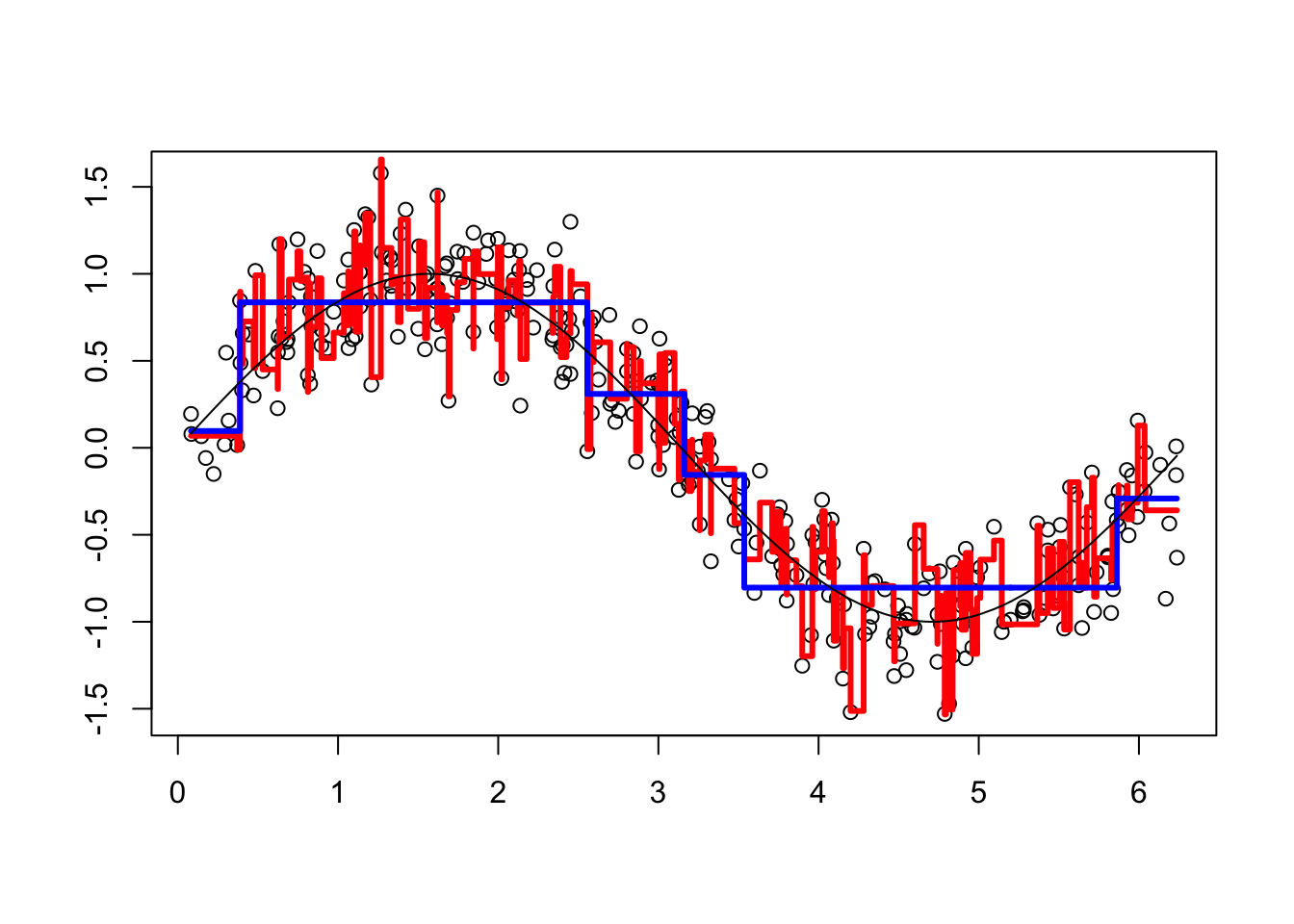

viz(101)

It overfits. Unlike random forests, boosting can overfit if the number of trees (B) and depth of each tree (D) are too large.

By averaging over a large number of trees, bagging and random forests reduces variability. Boosting does not average over the trees. This shows that \(h\) should be tuned by a cross-validation process. The generalized boosted regression modeling (GBM) (Ridgeway 2020) can be used for boosted regressions. Note that there are many arguments with their specific default values in the function. For example, n.tree (\(B\)) is 100 and shrinkage (\(h\)) is 0.1. interaction.depth, \(D\), specifying the maximum depth of each tree, is 1, which implies an additive model (2 implies a model with up to 2-way interactions). A smaller \(h\) typically requires more trees \(B\). It allows more and different shaped trees to attack the residuals.

Here is the application of gbm() to our simulated data:

library(gbm)

# Note bag.fraction = 1 (no CV). The default is 0.5

bo1 <- gbm(y ~ x, distribution="gaussian", n.tree = 100, data = df,

shrinkage = 0.1, bag.fraction = 1)

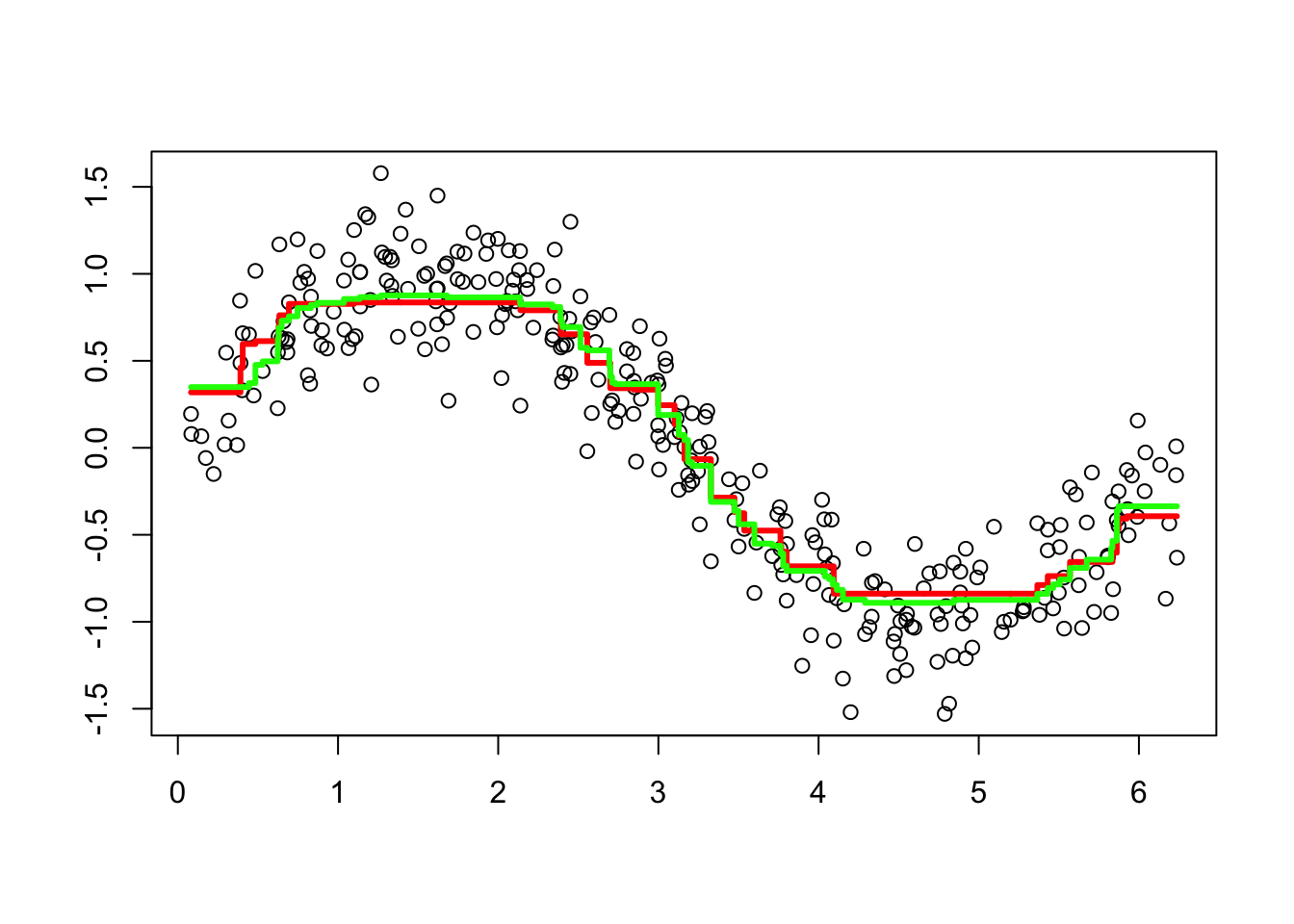

bo2 <- gbm(y ~ x, distribution="gaussian", data = df) # All default

plot(df$x, df$y, ylab="", xlab="") #Data points

lines(df$x, predict(bo1, data=df, n.trees=t), type="s",

col="red", lwd=3) #line for without CV

lines(df$x, predict(bo2, n.trees=t, data=df), type="s",

col="green", lwd=3) #line with default parameters with CV

Let’s see boosting for classification

13.3.2 AdaBoost

One of the most popular boosting algorithm is AdaBost.M1 due to Freund and Schpire (1997). We consider two-class problem where \(y \in\{-1,1\}\), which is a qualitative variable. With a set of predictor variables \(X\), a classifier \(\hat{m}_{b}(x)\) at tree b among B trees, produces a prediction taking the two values \(\{-1,1\}\).

To understand how AdaBoost works, let’s look at the algorithm step by step:

- Select the number of trees

B, and the tree depthD; - Set initial weights, \(w_i=1/n\), for each observation.

- Fit a classification tree \(\hat{m}_{b}(x)\) at \(b=1\), the first tree.

- Calculate the following misclassification error for \(b=1\):

\[ \mathbf{err}_{b=1}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \mathbf{I}\left(y_{i} \neq \hat{m}_{b}\left(x_{i}\right)\right)}{n} \]

- By using this error, calculate

\[ \alpha_{b}=0.5\log \left(\frac{1-e r r_{b}}{e r r_{b}}\right) \]

This gives us log odds. For example, suppose \(err_b = 0.3\), then \(\alpha_{b}=\text{log}(0.7/0.3)\), which is a log odds or log(success/failure).

- If the observation

iis misclassified, update its weights, if not, use \(w_i\) which is \(1/n\):

\[ w_{i} \leftarrow w_{i} e^{\alpha_b} \]

Let’s try some numbers:

#Suppose err = 0.2, n=100

n = 100

err = 0.2

alpha <- 0.5*log((1-err)/err)

alpha## [1] 0.6931472exp(alpha)## [1] 2So, the new weight for the misclassified \(i\) in the second tree (i.e., \(b=2\) stump) will be

# For misclassified obervations

weight_miss <- (1/n)*(exp(alpha))

weight_miss## [1] 0.02# For correctly classified observation

weight_corr <- (1/n)*(exp(-alpha))

weight_corr## [1] 0.005This shows that as the misclassification error goes up, it increases the weights (0.04) of each misclassified observation relative to correctly classified observations and reduces the weights for correctly classified observations (0.0025).

- With this procedure, in each loop from

btoB, it reapply \(\hat{m}_{b}(x)\) to the data using updated weights \(w_i\) in eachbby updating in weights by:

\[ \mathbf{err}_{b}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} w_{i} \mathbf{I}\left(y_{i} \neq \hat{m}_{b}\left(x_{i}\right)\right)}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} w_{i}} \]

We know that the sum of the weights are supposed to be 1. So a normalization for all weights between 0 and 1 would handle this issue in each iteration. The algorithm works in a way that it randomly replicates the observations as new data points by using the weights as their probabilities. This process also resembles to under- and oversampling at the same time so that the number of observations stays the same. The new dataset now is used again for the next tree (\(b=2\)) and this iteration continues until \(B\). We can use rpart() in each tree with weights option as we will shown momentarily.

Here is an example with the myocarde data that we used in CARD:

myocarde <- read_delim("myocarde.csv", delim = ";" ,

escape_double = FALSE, trim_ws = TRUE,

show_col_types = FALSE)

myocarde <- data.frame(myocarde)

df <- head(myocarde)

df$W = 1/nrow(df)

df## FRCAR INCAR INSYS PRDIA PAPUL PVENT REPUL PRONO W

## 1 90 1.71 19.0 16 19.5 16.0 912 SURVIE 0.1666667

## 2 90 1.68 18.7 24 31.0 14.0 1476 DECES 0.1666667

## 3 120 1.40 11.7 23 29.0 8.0 1657 DECES 0.1666667

## 4 82 1.79 21.8 14 17.5 10.0 782 SURVIE 0.1666667

## 5 80 1.58 19.7 21 28.0 18.5 1418 DECES 0.1666667

## 6 80 1.13 14.1 18 23.5 9.0 1664 DECES 0.1666667Suppose that our first stump misclassifies the first observation. So the error rate

# Alpha

n = nrow(df)

err = 1/n

alpha <- 0.5*log((1-err)/err)

alpha## [1] 0.804719exp(alpha)## [1] 2.236068# ****** Weights *******

# For misclassified obervations

weight_miss <- (1/n)*(exp(alpha))

weight_miss## [1] 0.372678# For correctly classified observation

weight_corr <- (1/n)*(exp(-alpha))

weight_corr## [1] 0.0745356Hence, our new sample weights

df$NW <- c(weight_miss, rep(weight_corr, 5))

df$Norm <- df$NW/sum(df$NW) # nromalizing

#Ignoring X's

df[,8:11]## PRONO W NW Norm

## 1 SURVIE 0.1666667 0.3726780 0.5

## 2 DECES 0.1666667 0.0745356 0.1

## 3 DECES 0.1666667 0.0745356 0.1

## 4 SURVIE 0.1666667 0.0745356 0.1

## 5 DECES 0.1666667 0.0745356 0.1

## 6 DECES 0.1666667 0.0745356 0.1Now, the new dataset:

df$bins <- cumsum(df$Norm)

df[,8:12]## PRONO W NW Norm bins

## 1 SURVIE 0.1666667 0.3726780 0.5 0.5

## 2 DECES 0.1666667 0.0745356 0.1 0.6

## 3 DECES 0.1666667 0.0745356 0.1 0.7

## 4 SURVIE 0.1666667 0.0745356 0.1 0.8

## 5 DECES 0.1666667 0.0745356 0.1 0.9

## 6 DECES 0.1666667 0.0745356 0.1 1.0Now supposed we run runif(n=6, min = 0, max = 1) and get \(0.2201686, 0.9465279, 0.5118751, 0.8167266, 0.2208179, 0.1183170.\) Since incorrectly classified records have higher sample weights, the probability to select those records is very high. We select the observation that these random numbers in their bin:

df[c(1,6,2,4,1,1), -c(9:12)] # after## FRCAR INCAR INSYS PRDIA PAPUL PVENT REPUL PRONO

## 1 90 1.71 19.0 16 19.5 16 912 SURVIE

## 6 80 1.13 14.1 18 23.5 9 1664 DECES

## 2 90 1.68 18.7 24 31.0 14 1476 DECES

## 4 82 1.79 21.8 14 17.5 10 782 SURVIE

## 1.1 90 1.71 19.0 16 19.5 16 912 SURVIE

## 1.2 90 1.71 19.0 16 19.5 16 912 SURVIEdf[,1:8] # before## FRCAR INCAR INSYS PRDIA PAPUL PVENT REPUL PRONO

## 1 90 1.71 19.0 16 19.5 16.0 912 SURVIE

## 2 90 1.68 18.7 24 31.0 14.0 1476 DECES

## 3 120 1.40 11.7 23 29.0 8.0 1657 DECES

## 4 82 1.79 21.8 14 17.5 10.0 782 SURVIE

## 5 80 1.58 19.7 21 28.0 18.5 1418 DECES

## 6 80 1.13 14.1 18 23.5 9.0 1664 DECESHence, observations that are misclassified will have more influence in the next classifier. This is an incredible boost that forces the classification tree to adjust its prediction to do better job for misclassified observations.

- Finally, in the output, the contributions from classifiers that fit the data better are given more weight (a larger \(\alpha_b\) means a better fit). Unlike a random forest algorithm where each tree gets an equal weight in final decision, here some stumps get more say in final classification. Moreover, “forest of stumps” the order of trees is important.

Hence, the final prediction on \(y_i\) will be combined from all trees, b to B, through a weighted majority vote:

\[ \hat{y}_{i}=\operatorname{sign}\left(\sum_{b=1}^{B} \alpha_{b} \hat{m}_{b}(x)\right), \]

which is a signum function defined as follows:

\[ \operatorname{sign}(x):=\left\{\begin{array}{ll} {-1} & {\text { if } x<0} \\ {0} & {\text { if } x=0} \\ {1} & {\text { if } x>0} \end{array}\right. \]

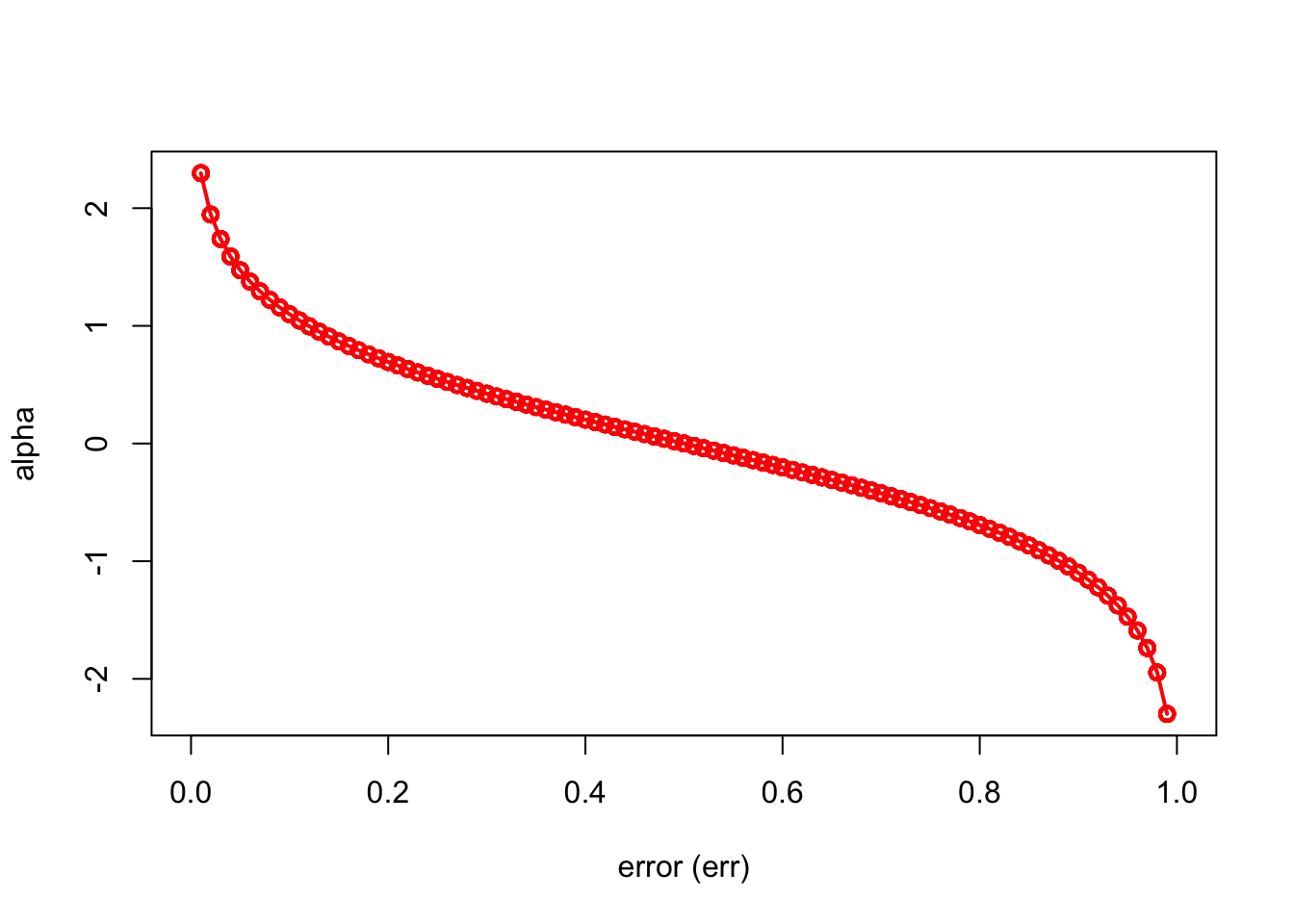

Here is a simple simulation to show how alpha will make the importance of each tree (\(\hat{m}_{b}(x)\)) different:

n = 1000

set.seed(1)

err <- sample(seq(0, 1, 0.01), n, replace = TRUE)

alpha = 0.5*log((1-err)/err)

ind = order(err)

plot(err[ind], alpha[ind], xlab = "error (err)", ylab = "alpha",

type = "o", col = "red", lwd = 2)

We can see that when there is no misclassification error (err = 0), “alpha” will be a large positive number. When the classifier very weak and predicts as good as a random guess (err = 0.5), the importance of the classifier will be 0. If all the observations are incorrectly classified (err = 1), our alpha value will be a negative integer.

The AdaBoost.M1 is known as a “discrete classifier” because it directly calculates discrete class labels \(\hat{y}_i\), rather than predicted probabilities, \(\hat{p}_i\).

What type of classifier, \(\hat{m}_{b}(x)\), would we choose? Usually a “weak classifier” like a “stump” (a two terminal-node classification tree, i.e 1 split) would be enough. The \(\hat{m}_{b}(x)\) choose one variable to form a stump that gives the lowest Gini index.

Here is our simple example with the myocarde data to show how we can boost a simple weak learner (stump) by using AdaBoost algorithm:

library(rpart)

# Data

myocarde <- read_delim("myocarde.csv", delim = ";" ,

escape_double = FALSE, trim_ws = TRUE,

show_col_types = FALSE)

myocarde <- data.frame(myocarde)

y <- (myocarde[ , "PRONO"] == "SURVIE") * 2 - 1

x <- myocarde[ , 1:7]

df <- data.frame(x, y)

# Setting

rnd = 100 # number of rounds

m = nrow(x)

W <- rep(1/m, m) # initial weights

S <- list() # container to save all stumps

alpha <- vector(mode = "numeric", rnd) # container for alpha

y_hat <- vector(mode = "numeric", m) # container for final predictions

set.seed(123)

for(i in 1:rnd) {

S[[i]] <- rpart(y ~., data = df, weights = W, maxdepth = 1, method = "class")

yhat <- predict(S[[i]], x, type = "class")

yhat <- as.numeric(as.character(yhat))

e <- sum((yhat!=y) * W)

# alpha

alpha[i] <- 0.5 * log((1-e) / e)

# Updating weights

W <- W * exp(-alpha[i] * y * yhat)

# Normalizing weights

W <- W / sum(W)

}

# Using each stump for S[i] for final predictions

for (i in 1:rnd) {

pred = predict(S[[i]], df, type = "class")

pred = as.numeric(as.character(pred))

y_hat = y_hat + (alpha[i] * pred)

}

# Let's see what y_hat is

y_hat## [1] 3.132649 -4.135656 -4.290437 7.547707 -3.118702 -6.946686

## [7] 2.551433 1.960603 9.363346 6.221990 3.012195 6.982287

## [13] 9.765139 8.053999 8.494254 7.454104 4.112493 5.838279

## [19] 4.918513 9.514860 9.765139 -3.519537 -3.172093 -7.134057

## [25] -3.066699 -4.539863 -2.532759 -2.490742 5.412605 2.903552

## [31] 2.263095 -6.718090 -2.790474 6.813963 -5.131830 3.680202

## [37] 3.495350 3.014052 -7.435835 6.594157 -7.435835 -6.838387

## [43] 3.951168 5.091548 -3.594420 8.237515 -6.718090 -9.582674

## [49] 2.658501 -10.282682 4.490239 9.765139 -5.891116 -5.593352

## [55] 6.802687 -2.059754 2.832103 7.655197 10.635851 9.312842

## [61] -5.804151 2.464149 -5.634676 1.938855 9.765139 7.023157

## [67] -6.078756 -7.031840 5.651634 -1.867942 9.472835# Now use sign() function

pred <- sign(y_hat)

# Confusion matrix

table(pred, y)## y

## pred -1 1

## -1 29 0

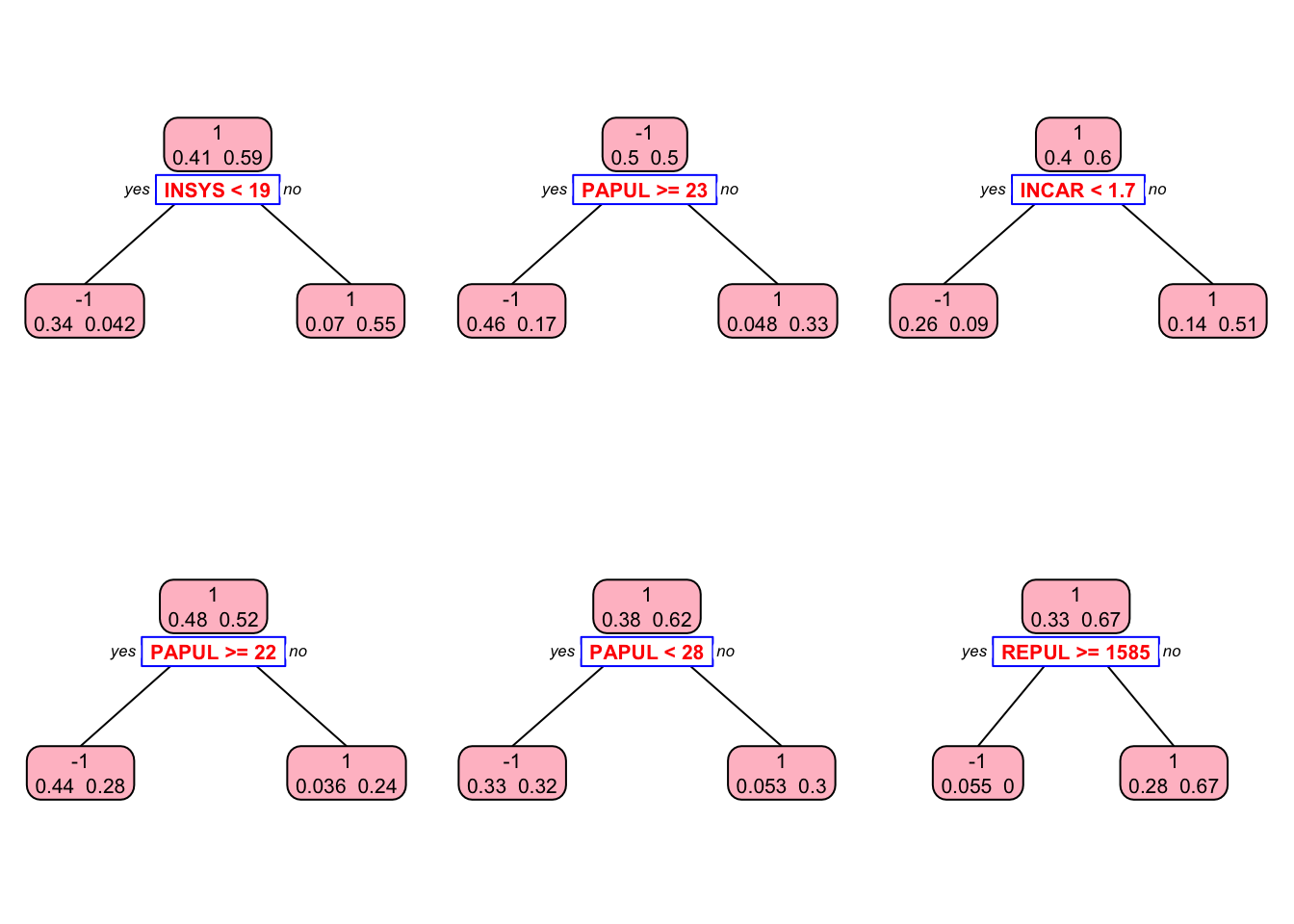

## 1 0 42This is our in-sample confusion table. We can also see several stumps:

library(rpart.plot)

plt <- c(1,5,10,30, 60, 90)

p = par(mfrow=c(2,3))

for(i in 1:length(plt)){

prp(S[[i]], type = 2, extra = 1, split.col = "red",

split.border.col = "blue", box.col = "pink")

}

par(p)Let’s see it with the JOUSBoost package:

library(JOUSBoost)

ada <- adaboost(as.matrix(x), y, tree_depth = 1, n_rounds = rnd)

summary(ada)## Length Class Mode

## alphas 100 -none- numeric

## trees 100 -none- list

## tree_depth 1 -none- numeric

## terms 3 terms call

## confusion_matrix 4 table numericpred <- predict(ada, x)

table(pred, y)## y

## pred -1 1

## -1 29 0

## 1 0 42These results provide in-sample predictions. When we use it in a real example, we can train AdaBoost.M1 by the tree depths (1 in our example) and the number of iterations (100 trees in our example). Although, there are simulations that AdaBoost is stubbornly resistant to overfitting, you can try with different tree depth and number of trees.

An application is provided in the next chapter.

13.3.3 Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) the most efficient version of the gradient boosting framework by its capacity to implement parallel computation on a single machine. It can be used for regression and classification problems with two modes: linear models and tree learning algorithm. This is important because, as we will see in the next section (and Section 6), XGBoost can be used for regularization in linear models. As always, however, decision trees are much better to catch a nonlinear link between predictors and outcome. Thus, comparison between two methods can provide quick information to the practitioner, specially in causal analyses, about the structure of alternative models.

The XGBoost has several unique advantages: its speed is measured as “10 times faster than the gbm” (see its vignette) and it accepts very efficient input data structures, such as a sparse matrix13. This special input structure in xgboost requires some additional data preparation: a matrix input for the features and a vector for the response. Therefore, a matrix input of the features requires to encode our categorical variables, as we showed before. The matrix can also be selected 3 possible choices: a regular R matrix, a sparse matrix from the Matrix package,

We will use a regression example here and leave the classification example to the next chapter in boosting applications. We will use the Ames housing data to see the best “predictors” of the sale price.

library(xgboost)

library(mltools)

library(data.table)

library(modeldata) # This can also be loaded by the tidymodels package

data(ames)

#str(ames)

dim(ames)## [1] 2930 74The xgboost algorithm accepts its input data as a matrix. Therefore all the categorical variables have be one-hot coded, which creates a large matrix with even with a small size data. That’s why using more memory efficient matrix types (sparse matrix etc.) speeds up the process. We ignore it here and use a regular R matrix, for now.

ames_new <- one_hot(as.data.table(ames))

df <- as.data.frame(ames_new)

ind <- sample(nrow(df), nrow(df), replace = TRUE)

train <- df[ind, ]

test <- df[-ind, ]

X <- as.matrix(train[, -which(names(train) == "Sale_Price")])

Y <- train$Sale_PriceNow we are ready for finding the optimal tuning parameters. One strategy in tuning is to see if there is a substantial difference between train and CV errors. As we have seen in gbm, we first start with the number trees and the learning rate. If the difference still persists, we introduce regularization parameters. There are three regularization parameters: gamma, lambda, and alpha. The last two are similar to what we will see in a linear regularization next chapter. Let’s start with the data preparation as xgboost requires a matrix input for the features and a vector for the response. We will do it without a grid search. This should be done with sweeping a grid of hyperparamaters (including gamma, lambda, and alpha):

set.seed(123)

boost <- xgb.cv(

data = X,

label = Y,

nrounds = 3000,

objective = "reg:squarederror",

early_stopping_rounds = 50,

nfold = 10,

params = list(

eta = 0.1,

max_depth = 3,

min_child_weight = 3,

subsample = 0.8,

colsample_bytree = 1.0),

verbose = 0

) Let’s see the RMSE and the best iteration:

boost$best_iteration## [1] 1781min(boost$evaluation_log$test_rmse_mean)## [1] 16807.16# One possible grid would be:

# param_grid <- expand.grid(

# eta = 0.01,

# max_depth = 3,

# min_child_weight = 3,

# subsample = 0.5,

# colsample_bytree = 0.5,

# gamma = c(0, 1, 10, 100, 1000),

# lambda = seq(0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 100, 1000),

# alpha = c(0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 100, 1000)

# )

# After going through the grid in a loop with `xgb.cv`

# we save multiple `test_rmse_mean` and `best_iteration`

# and find the parameters that gives the minimum rmseNow after identifying the best model, we can use it on the test data:

params <- list(

eta = 0.01,

max_depth = 3,

min_child_weight = 3,

subsample = 0.8,

colsample_bytree = 1.0

)

tr_model <- xgboost(

params = params,

data = X,

label = Y,

nrounds = 2515,

objective = "reg:squarederror",

verbose = 0

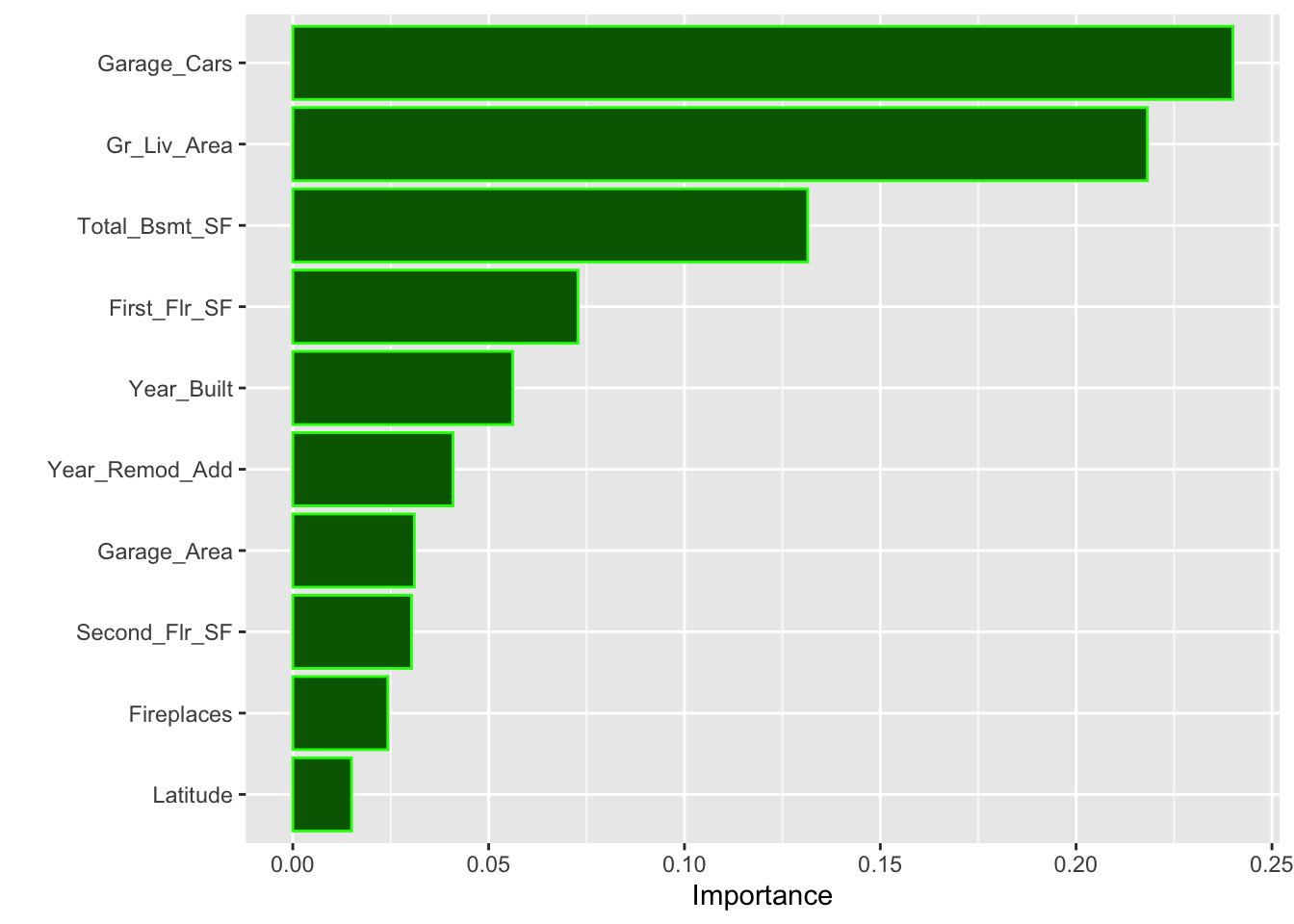

)This trained (best fitting model) is enough to obtain the top 10 influential features in our final model using the impurity (gain) metric:

library(vip)

vip(tr_model,

aesthetics = list(color = "green", fill = "darkgreen"))

Now, we can use our trained model for predictions using our test set. Note that, again, xgboost would only accept matrix inputs.

yhat <- predict(tr_model,

as.matrix(test[,-which(names(test) == "Sale_Price")]))

rmse_test <- sqrt(mean((test[,which(names(train) == "Sale_Price")]-yhat)^2))

rmse_test## [1] 22895.51Note the big difference between training and test RMSPE’s. This is an indication that our “example” grid is not doing a good job. We should include regularization tuning parameters and run a full scale grid search.

We will look at a classification example in the next chapter (Ch.13). But, a curious reader would ask: would it be better had we run random forest? Or, could it have been better with a full scale grid search?

References

https://web.archive.org/web/20121010030839/http://www.cs.princeton.edu/~schapire/papers/strengthofweak.pdf↩︎

In a sparse matrix, cells containing 0 are not stored in memory. Therefore, in a dataset mainly made of 0, the memory size is reduced.↩︎