Chapter 28 Principle Component Analysis

Having seen SVD and Eigenvalue decomposition, now we can look at Principle Component Analysis (PCA), which is a statistical procedure that allows you to summarize the information content in large data tables. In other words, it helps dimension reduction in big datasets.

PCA is a eigenvalue decomposition of a covariance matrix (of data matrix \(\mathbf{X}\)). Since a covariance matrix is a square matrix, we can apply the eigenvalue decomposition, which reveals the unique orthogonal directions (variances) in the data so that their orthogonal linear combinations maximize the total variance.

The goal is here a dimension reduction of the data matrix. Hence by selecting a few loading, we can reduce the dimension of the data but capture a substantial variation in the data at the same time. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fkf4IBRSeEc (Brunton 2020a) and https://setosa.io/ev/principal-component-analysis/ (Powell 2017).

Principal components are the ordered (orthogonal) lines (vectors) that best account for the maximum variance in the data by their magnitude. To get the (unique) variances (direction and the magnitude) in data, we first obtain the mean-centered covariance matrix. And as you can imagine, eigenvectors (which give the unique directions) and eigenvalues (which identify those directions’ magnitude) are used for PCA:

So when we use the covariance matrix of a data, we can use eigenvalue decomposition to identify the unique variation and their relative magnitude in the data. Here is a simple procedure:

- \(\mathbf{X}\) is the data matrix,

- \(\mathbf{B}\) is the mean-centered data matrix,

- \(\mathbf{C}\) is the covariance matrix (\(\mathbf{B^TB}\)) (note if \(\mathbf{B}\) is scaled, i.e. “z-scored”, \(\mathbf{B^TB}\) gives correlation matrix)

- Compute the eigenvectors and values of \(\mathbf{C}\): \(\mathbf{C} = \mathbf{VDV^{\top}}\) hence \(\mathbf{CV} = \mathbf{VD}\), where \(\mathbf{V}\) is the eigenvectors (loadings) and \(\mathbf{D}\) is eigenvalues.

- Using \(\mathbf{V}\), the transformation of \(\mathbf{B}\) with \(\mathbf{B} \mathbf{V}\) maps the data of \(p\) variables to a new space of \(p\) variables which are uncorrelated over the dataset. \(\mathbf{T} (=\mathbf{B} \mathbf{V})\) is called the principle component or score matrix

- Since SVD of \(\mathbf{B} = \mathbf{U} \Sigma \mathbf{V}^{\top}\), we can also get \(\mathbf{B}\mathbf{V} = \mathbf{T} = \mathbf{U\Sigma}\). Hence the principle components are \(\mathbf{T} = \mathbf{BV} = \mathbf{U\Sigma}\).

- However, not all the principal components need to be kept. Keeping only the first \(r\) principal components, produced by using only the first \(r\) eigenvectors, gives the truncated transformation \(\mathbf{T}_{r} = \mathbf{B} \mathbf{V}_{r}\). Obviously you choose those with higher variance in each directions by the order of eigenvalues.

- We can use \(\frac{\lambda_{k}}{\sum_{i=1} \lambda_{k}}\) to identify \(r\). Or cumulatively, we can see how much variation could be captured by \(r\) number of \(\lambda\)s, which gives us an idea how many principle components to keep …

\[ \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{r} \lambda_{k}}{\sum_{i=1}^n \lambda_{k}} \]

Let’s see an example. Here is the data:

library("factoextra")

data(decathlon2)

X <- as.matrix(decathlon2[, 1:10])

head(X)## X100m Long.jump Shot.put High.jump X400m X110m.hurdle Discus

## SEBRLE 11.04 7.58 14.83 2.07 49.81 14.69 43.75

## CLAY 10.76 7.40 14.26 1.86 49.37 14.05 50.72

## BERNARD 11.02 7.23 14.25 1.92 48.93 14.99 40.87

## YURKOV 11.34 7.09 15.19 2.10 50.42 15.31 46.26

## ZSIVOCZKY 11.13 7.30 13.48 2.01 48.62 14.17 45.67

## McMULLEN 10.83 7.31 13.76 2.13 49.91 14.38 44.41

## Pole.vault Javeline X1500m

## SEBRLE 5.02 63.19 291.7

## CLAY 4.92 60.15 301.5

## BERNARD 5.32 62.77 280.1

## YURKOV 4.72 63.44 276.4

## ZSIVOCZKY 4.42 55.37 268.0

## McMULLEN 4.42 56.37 285.1n <- nrow(X)

B <- scale(X, center = TRUE)

C <- t(B)%*%B/(n-1)

head(C)## X100m Long.jump Shot.put High.jump X400m

## X100m 1.0000000 -0.7377932 -0.3703180 -0.3146495 0.5703453

## Long.jump -0.7377932 1.0000000 0.3737847 0.2682078 -0.5036687

## Shot.put -0.3703180 0.3737847 1.0000000 0.5747998 -0.2073588

## High.jump -0.3146495 0.2682078 0.5747998 1.0000000 -0.2616603

## X400m 0.5703453 -0.5036687 -0.2073588 -0.2616603 1.0000000

## X110m.hurdle 0.6699790 -0.5521158 -0.2701634 -0.2022579 0.5970140

## X110m.hurdle Discus Pole.vault Javeline X1500m

## X100m 0.6699790 -0.3893760 0.01156433 -0.26635476 -0.17805307

## Long.jump -0.5521158 0.3287652 0.07982045 0.28806781 0.17332597

## Shot.put -0.2701634 0.7225179 -0.06837068 0.47558572 0.00959628

## High.jump -0.2022579 0.4210187 -0.55129583 0.21051789 -0.15699017

## X400m 0.5970140 -0.2545326 0.11156898 0.02350554 0.18346035

## X110m.hurdle 1.0000000 -0.4213608 0.12118697 0.09655757 -0.10331329#Check it

head(cov(B))## X100m Long.jump Shot.put High.jump X400m

## X100m 1.0000000 -0.7377932 -0.3703180 -0.3146495 0.5703453

## Long.jump -0.7377932 1.0000000 0.3737847 0.2682078 -0.5036687

## Shot.put -0.3703180 0.3737847 1.0000000 0.5747998 -0.2073588

## High.jump -0.3146495 0.2682078 0.5747998 1.0000000 -0.2616603

## X400m 0.5703453 -0.5036687 -0.2073588 -0.2616603 1.0000000

## X110m.hurdle 0.6699790 -0.5521158 -0.2701634 -0.2022579 0.5970140

## X110m.hurdle Discus Pole.vault Javeline X1500m

## X100m 0.6699790 -0.3893760 0.01156433 -0.26635476 -0.17805307

## Long.jump -0.5521158 0.3287652 0.07982045 0.28806781 0.17332597

## Shot.put -0.2701634 0.7225179 -0.06837068 0.47558572 0.00959628

## High.jump -0.2022579 0.4210187 -0.55129583 0.21051789 -0.15699017

## X400m 0.5970140 -0.2545326 0.11156898 0.02350554 0.18346035

## X110m.hurdle 1.0000000 -0.4213608 0.12118697 0.09655757 -0.10331329Eigenvalues and vectors …

#Eigens

evalues <- eigen(C)$values

evalues## [1] 3.7499727 1.7451681 1.5178280 1.0322001 0.6178387 0.4282908 0.3259103

## [8] 0.2793827 0.1911128 0.1122959evectors <- eigen(C)$vectors

evectors #Ordered## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

## [1,] 0.42290657 -0.2594748 -0.081870461 -0.09974877 0.2796419 -0.16023494

## [2,] -0.39189495 0.2887806 0.005082180 0.18250903 -0.3355025 -0.07384658

## [3,] -0.36926619 -0.2135552 -0.384621732 -0.03553644 0.3544877 -0.32207320

## [4,] -0.31422571 -0.4627797 -0.003738604 -0.07012348 -0.3824125 -0.52738027

## [5,] 0.33248297 -0.1123521 -0.418635317 -0.26554389 -0.2534755 0.23884715

## [6,] 0.36995919 -0.2252392 -0.338027983 0.15726889 -0.2048540 -0.26249611

## [7,] -0.37020078 -0.1547241 -0.219417086 -0.39137188 0.4319091 0.28217086

## [8,] 0.11433982 0.5583051 -0.327177839 0.24759476 0.3340758 -0.43606610

## [9,] -0.18341259 -0.0745854 -0.564474643 0.47792535 -0.1697426 0.42368592

## [10,] -0.03599937 0.4300522 -0.286328973 -0.64220377 -0.3227349 -0.10850981

## [,7] [,8] [,9] [,10]

## [1,] 0.03227949 -0.35266427 0.71190625 -0.03272397

## [2,] -0.24902853 -0.72986071 0.12801382 -0.02395904

## [3,] -0.23059438 0.01767069 -0.07184807 0.61708920

## [4,] -0.03992994 0.25003572 0.14583529 -0.41523052

## [5,] -0.69014364 0.01543618 -0.13706918 -0.12016951

## [6,] 0.42797378 -0.36415520 -0.49550598 0.03514180

## [7,] 0.18416631 -0.26865454 -0.18621144 -0.48037792

## [8,] -0.12654370 0.16086549 -0.02983660 -0.40290423

## [9,] 0.23324548 0.19922452 0.33300936 -0.02100398

## [10,] 0.34406521 0.09752169 0.19899138 0.18954698Now with prcomp(). First, eigenvalues:

# With `prcomp()`

Xpca <- prcomp(X, scale = TRUE)

#Eigenvalues

Xpca$sdev # you can see it's ordered## [1] 1.9364846 1.3210481 1.2320016 1.0159725 0.7860272 0.6544393 0.5708855

## [8] 0.5285666 0.4371645 0.3351059# They are sqrt() of eigenvalues that we calculated earlier

sqrt(evalues)## [1] 1.9364846 1.3210481 1.2320016 1.0159725 0.7860272 0.6544393 0.5708855

## [8] 0.5285666 0.4371645 0.3351059Loadings …

#Eigenvectors (loadings)

Xpca$rotation # 10x10## PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5

## X100m -0.42290657 0.2594748 -0.081870461 0.09974877 -0.2796419

## Long.jump 0.39189495 -0.2887806 0.005082180 -0.18250903 0.3355025

## Shot.put 0.36926619 0.2135552 -0.384621732 0.03553644 -0.3544877

## High.jump 0.31422571 0.4627797 -0.003738604 0.07012348 0.3824125

## X400m -0.33248297 0.1123521 -0.418635317 0.26554389 0.2534755

## X110m.hurdle -0.36995919 0.2252392 -0.338027983 -0.15726889 0.2048540

## Discus 0.37020078 0.1547241 -0.219417086 0.39137188 -0.4319091

## Pole.vault -0.11433982 -0.5583051 -0.327177839 -0.24759476 -0.3340758

## Javeline 0.18341259 0.0745854 -0.564474643 -0.47792535 0.1697426

## X1500m 0.03599937 -0.4300522 -0.286328973 0.64220377 0.3227349

## PC6 PC7 PC8 PC9 PC10

## X100m 0.16023494 -0.03227949 0.35266427 -0.71190625 0.03272397

## Long.jump 0.07384658 0.24902853 0.72986071 -0.12801382 0.02395904

## Shot.put 0.32207320 0.23059438 -0.01767069 0.07184807 -0.61708920

## High.jump 0.52738027 0.03992994 -0.25003572 -0.14583529 0.41523052

## X400m -0.23884715 0.69014364 -0.01543618 0.13706918 0.12016951

## X110m.hurdle 0.26249611 -0.42797378 0.36415520 0.49550598 -0.03514180

## Discus -0.28217086 -0.18416631 0.26865454 0.18621144 0.48037792

## Pole.vault 0.43606610 0.12654370 -0.16086549 0.02983660 0.40290423

## Javeline -0.42368592 -0.23324548 -0.19922452 -0.33300936 0.02100398

## X1500m 0.10850981 -0.34406521 -0.09752169 -0.19899138 -0.18954698loadings <- Xpca$rotationInterestingly the signs of eigenvectors are flipped and opposites of what we calculated with eigen() above. There are multiple discussions about the sign reversals in eignevectores. You can find them here (DU 2020) and here (Wilks 2019)

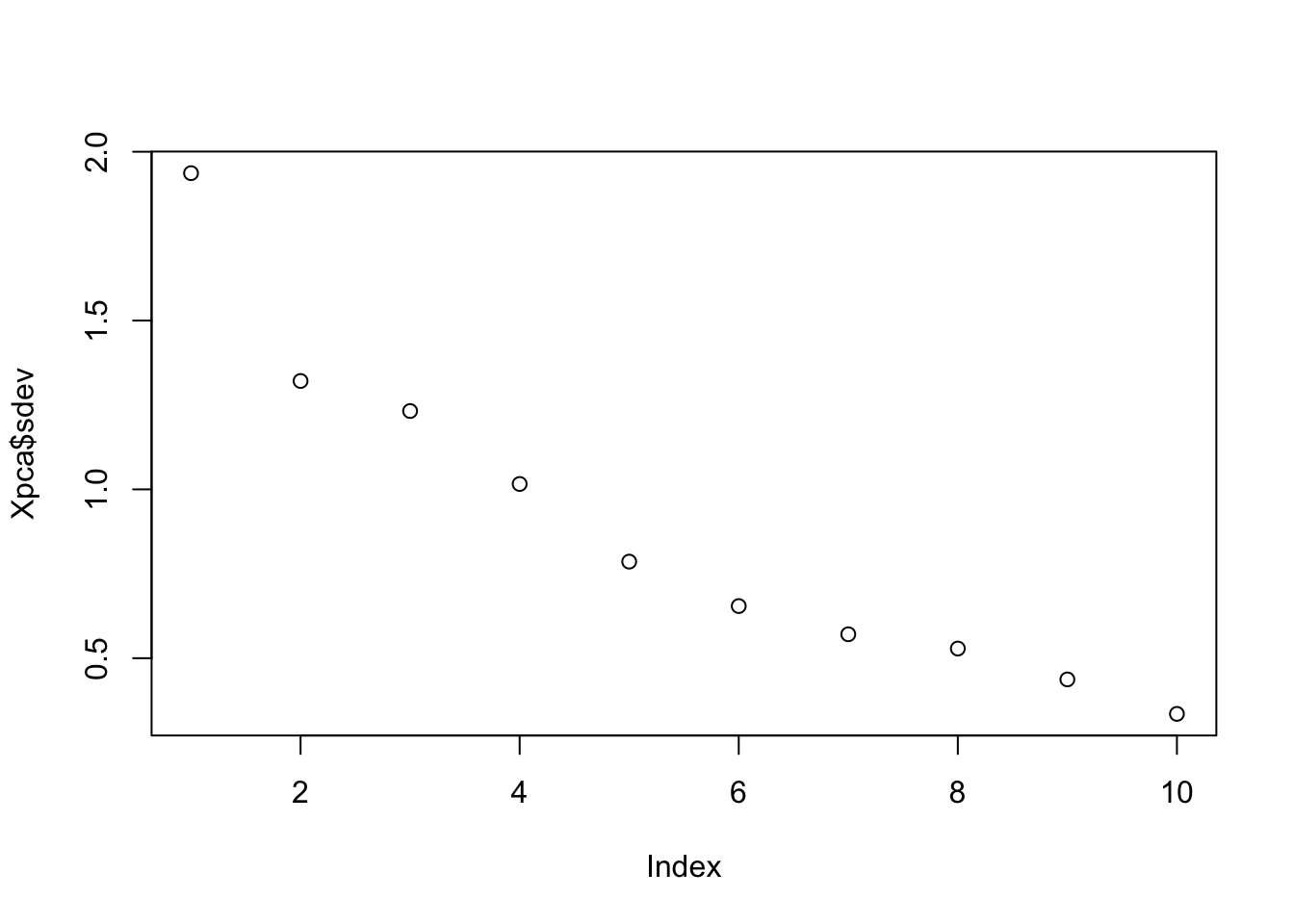

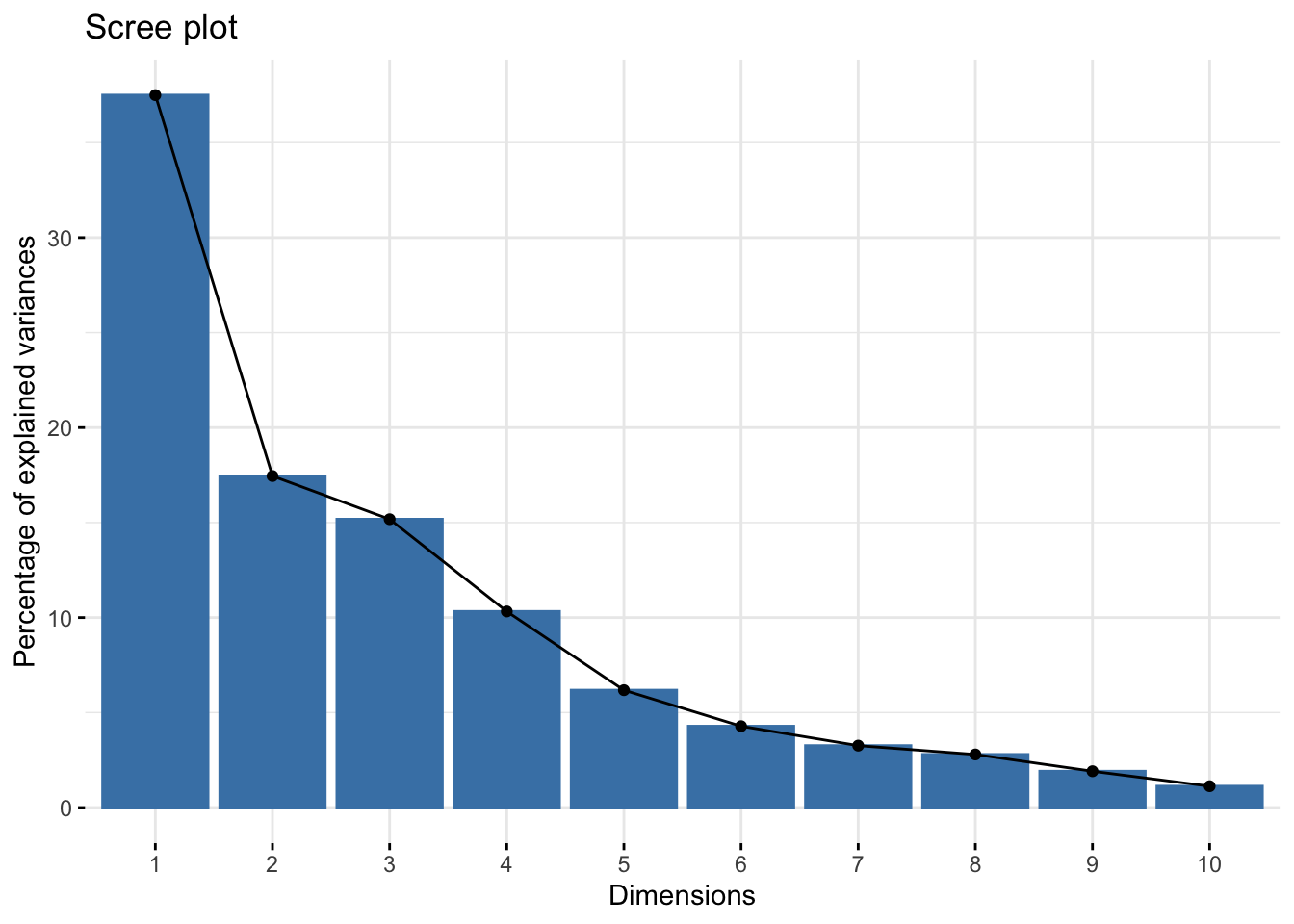

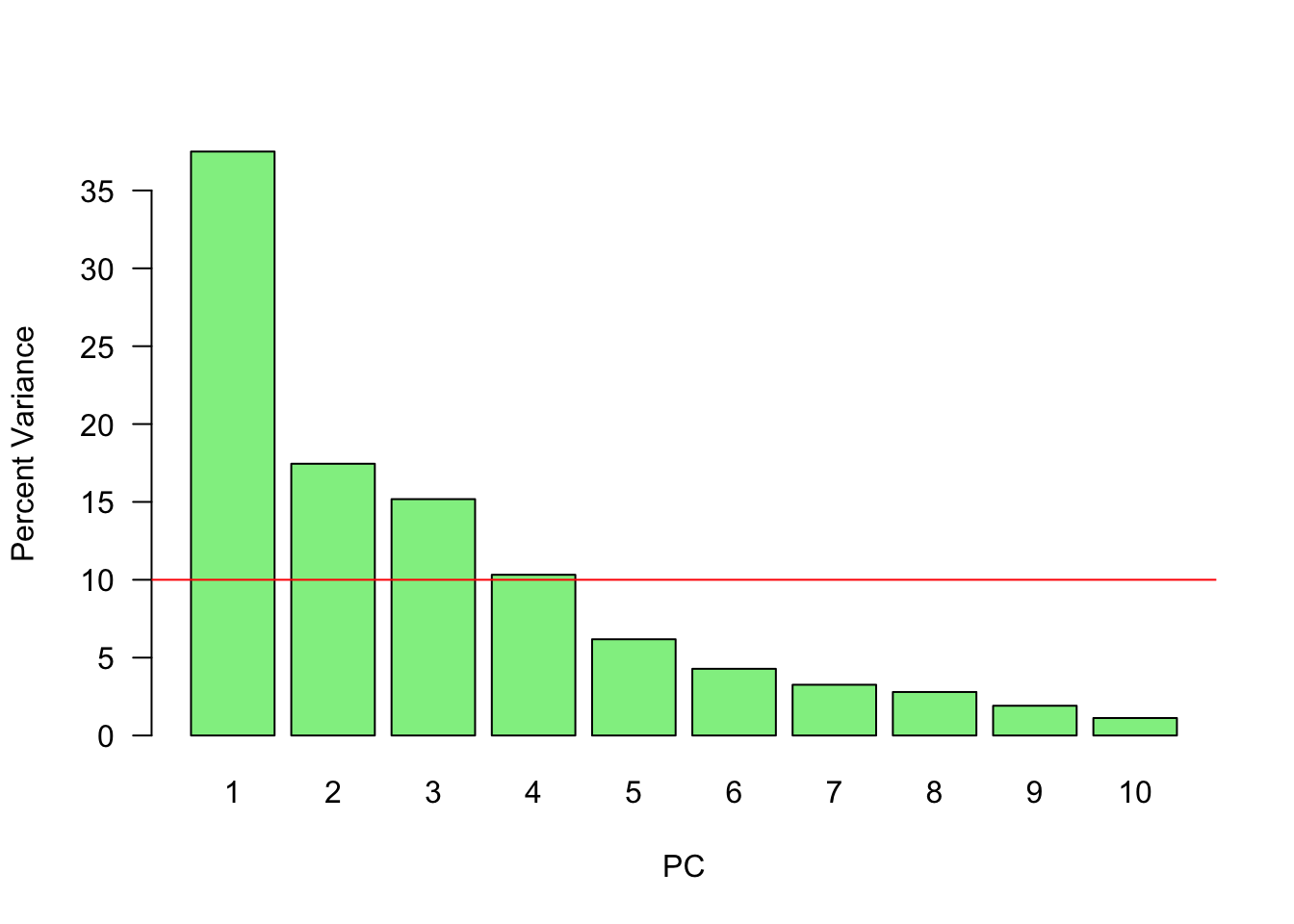

Visualize the order …

plot(Xpca$sdev) # Eigenvalues

fviz_eig(Xpca) # Cumulative with "factoextra"

# Or

var <- (Xpca$sdev)^2

var_perc <- var/sum(var) * 100

barplot(var_perc, xlab='PC', ylab='Percent Variance',

names.arg=1:length(var_perc), las=1,

ylim=c(0, max(var_perc)), col='lightgreen')

abline(h=mean(var_perc), col='red')

Since we have ten variables, if each variable contributed equally, they would each contribute 10% to the total variance (red line). This criterion suggests we should also include principal component 4 (but barely) in our interpretation.

And principle component scores \(\mathbf{T} = \mathbf{X}\mathbf{V}\) (a.k.a score matrix) with prcomp():

pc <- scale(X)%*%Xpca$rotation

head(pc)## PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5 PC6

## SEBRLE 0.2727622 -0.5264068 -1.5556058 0.10384438 1.05453531 0.7177257

## CLAY 0.8879389 -2.0551314 -0.8249697 1.81612193 -0.40100595 -1.5039874

## BERNARD -1.3466138 -1.3229149 -0.9439501 -1.46516144 -0.17925232 0.5996203

## YURKOV -0.9108536 2.2390912 -1.9063730 0.09501304 0.18735823 0.3754439

## ZSIVOCZKY -0.1018764 1.0694498 2.0596722 0.07056229 -0.03232182 -0.9321431

## McMULLEN 0.2353742 0.9215376 0.8028425 1.17942532 1.79598700 -0.3241881

## PC7 PC8 PC9 PC10

## SEBRLE -0.04935537 0.02990462 -0.63079187 0.07728655

## CLAY -0.75968352 -0.06536612 0.05920672 0.15812336

## BERNARD -0.75032098 -0.49570997 0.07483747 -0.03288604

## YURKOV -0.29565551 0.09332310 -0.06769776 0.13791531

## ZSIVOCZKY -0.30752133 0.29476740 -0.48055837 0.44234659

## McMULLEN 0.02896393 -0.53358562 0.05116850 0.37610188dim(pc)## [1] 27 10# which is also given by `prcomp()`

head(Xpca$x)## PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5 PC6

## SEBRLE 0.2727622 -0.5264068 -1.5556058 0.10384438 1.05453531 0.7177257

## CLAY 0.8879389 -2.0551314 -0.8249697 1.81612193 -0.40100595 -1.5039874

## BERNARD -1.3466138 -1.3229149 -0.9439501 -1.46516144 -0.17925232 0.5996203

## YURKOV -0.9108536 2.2390912 -1.9063730 0.09501304 0.18735823 0.3754439

## ZSIVOCZKY -0.1018764 1.0694498 2.0596722 0.07056229 -0.03232182 -0.9321431

## McMULLEN 0.2353742 0.9215376 0.8028425 1.17942532 1.79598700 -0.3241881

## PC7 PC8 PC9 PC10

## SEBRLE -0.04935537 0.02990462 -0.63079187 0.07728655

## CLAY -0.75968352 -0.06536612 0.05920672 0.15812336

## BERNARD -0.75032098 -0.49570997 0.07483747 -0.03288604

## YURKOV -0.29565551 0.09332310 -0.06769776 0.13791531

## ZSIVOCZKY -0.30752133 0.29476740 -0.48055837 0.44234659

## McMULLEN 0.02896393 -0.53358562 0.05116850 0.37610188Now you can think that if we use evectors that we calculated earlier with filliped signs, the data would be different. It’s similar to multiply the entire data with -1. So the data would not change in a sense that that captures the variation between observations and variables. That’s why the sign of eigenvalues are arbitraray.

With SVD …

# With SVD

Xsvd <- svd(scale(X))

pc_2 <- Xsvd$u%*%diag(Xsvd$d)

dim(pc_2)## [1] 27 10head(pc_2)## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

## [1,] 0.2727622 -0.5264068 -1.5556058 0.10384438 1.05453531 0.7177257

## [2,] 0.8879389 -2.0551314 -0.8249697 1.81612193 -0.40100595 -1.5039874

## [3,] -1.3466138 -1.3229149 -0.9439501 -1.46516144 -0.17925232 0.5996203

## [4,] -0.9108536 2.2390912 -1.9063730 0.09501304 0.18735823 0.3754439

## [5,] -0.1018764 1.0694498 2.0596722 0.07056229 -0.03232182 -0.9321431

## [6,] 0.2353742 0.9215376 0.8028425 1.17942532 1.79598700 -0.3241881

## [,7] [,8] [,9] [,10]

## [1,] -0.04935537 0.02990462 -0.63079187 0.07728655

## [2,] -0.75968352 -0.06536612 0.05920672 0.15812336

## [3,] -0.75032098 -0.49570997 0.07483747 -0.03288604

## [4,] -0.29565551 0.09332310 -0.06769776 0.13791531

## [5,] -0.30752133 0.29476740 -0.48055837 0.44234659

## [6,] 0.02896393 -0.53358562 0.05116850 0.37610188Here we can reduce the dimensionality by selecting only 4 PC (the first 4 PC’s are above the average, which explain more than 80% of the variation in the data - see the graph above)

reduced <- pc[, 1:4]

dim(reduced)## [1] 27 4head(reduced)## PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

## SEBRLE 0.2727622 -0.5264068 -1.5556058 0.10384438

## CLAY 0.8879389 -2.0551314 -0.8249697 1.81612193

## BERNARD -1.3466138 -1.3229149 -0.9439501 -1.46516144

## YURKOV -0.9108536 2.2390912 -1.9063730 0.09501304

## ZSIVOCZKY -0.1018764 1.0694498 2.0596722 0.07056229

## McMULLEN 0.2353742 0.9215376 0.8028425 1.17942532The individual columns of \(\mathbf{T}\) successively inherit the maximum possible variance from \(\mathbf{X}\), with each coefficient vector in \(\mathbf{V}\) constrained to be a unit vector. The full principal components decomposition of \(\mathbf{X}\), \(\mathbf{T}=\mathbf{X V}\), where \(\mathbf{V}\) is a \(p \times p\) matrix of weights whose columns are the eigenvectors of \(\mathbf{X}^{\top} \mathbf{X}\). Columns of \(\mathbf{V}\) multiplied by the square root of corresponding eigenvalues, that is, eigenvectors scaled up by the variances, are called loadings in PCA or in Factor analysis.

Note that if we make a singular value decomposition for a covariance matrix

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbf{X}^{T} \mathbf{X} &=\mathbf{V} \mathbf{\Sigma}^{\top} \mathbf{U}^{\top} \mathbf{U} \mathbf{\Sigma} \mathbf{V}^{\top} \\ &=\mathbf{V} \mathbf{\Sigma}^{\top} \mathbf{\Sigma} \mathbf{V}^{\top} \\ &=\mathbf{V} \hat{\mathbf{\Sigma}}^{2} \mathbf{V}^{\top} \end{aligned} \]

where \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}\) is the square diagonal matrix with the singular values of \(\mathbf{X}\) and the excess zeros chopped off that satisfies \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}^{2}=\boldsymbol{\Sigma}^{\top} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\).

Comparison with the eigenvector factorization of \(\mathbf{X}^{\top} \mathbf{X}\) establishes that the right singular vectors \(\mathbf{V}\) of \(\mathbf{X}\) are equivalent to the eigenvectors of \(\mathbf{X}^{\top} \mathbf{X}\), while the singular values \(\sigma_{(k)}\) of \(\mathbf{X}\) are equal to the square-root of the eigenvalues \(\lambda_{(k)}\) of \(\mathbf{X}^{\top} \mathbf{X}\).

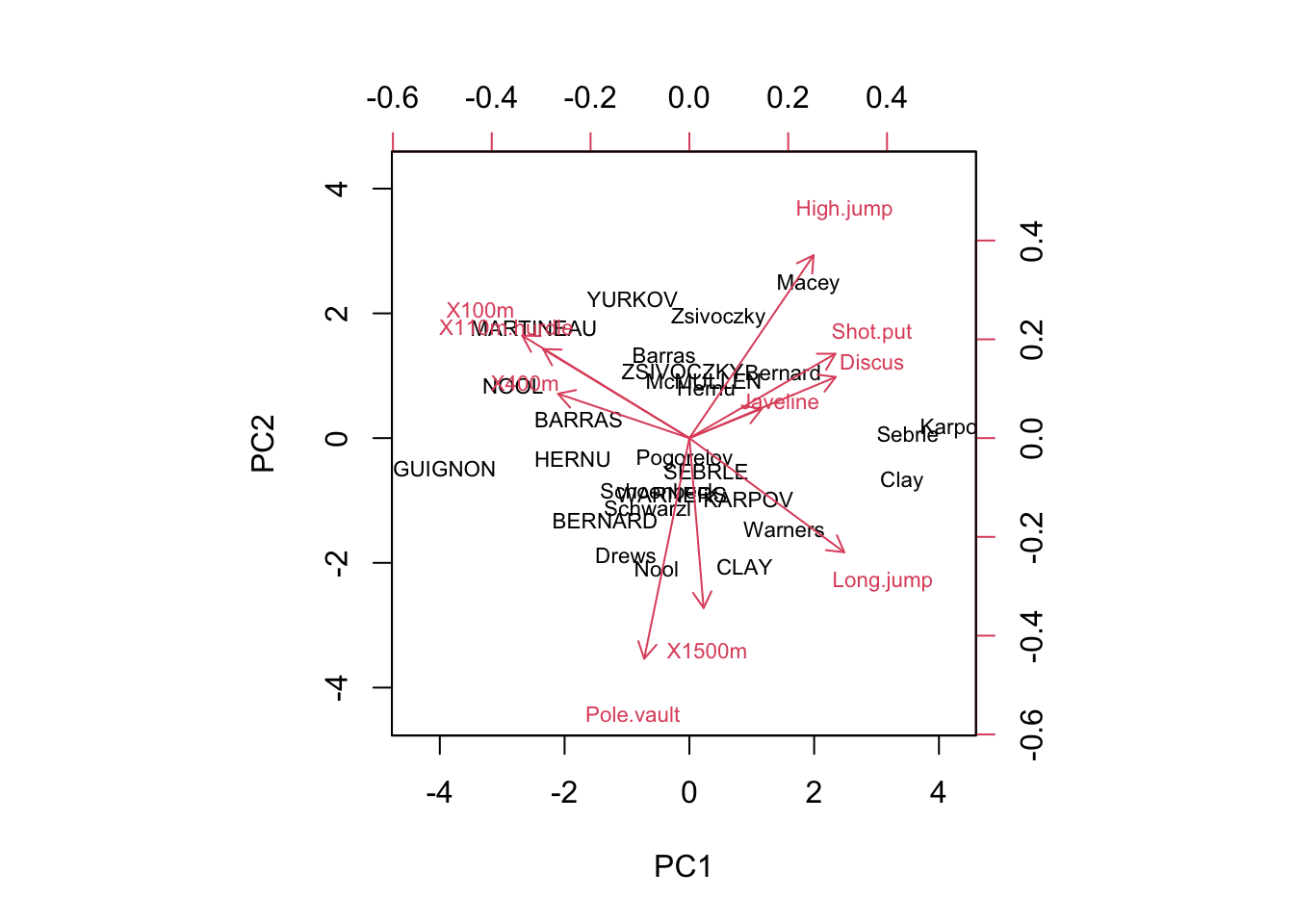

biplot(reduced[, 1:2], loadings[, 1:2], cex=0.7)